I’m in Memphis, Tennessee to watch my daughter play in a volleyball tournament, which means I’ve heard “The Star Spangled Banner” multiple times this weekend.

My relationship with our national anthem has been rocky, starting with my struggle to learn it as a kid. Something about the way the lines were written made it hard for me to memorize. (I now know why; I’ll get to that shortly.) When I finally grasped it, I belted it out proudly for decades.

Eventually, though, my ardor faded. I became disgusted with the United States, for many reasons: the Iraq war and all the subsequent endless wars we funded and made up excuses to instigate; the Guantanamo Bay atrocities; the arrest of Julian Assange… you get the picture.

Embarrassed by our actions and ashamed to call myself an American, I thought our bellicose anthem was emblematic of a belligerent nation. Like others, I thought we should adopt a more amicable, beatific song like “America the Beautiful” or “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” to represent us.

So for all those reasons and many more, I chose not to sing it in a sort of silent, unnoticed protest.

Fast-forward to now, in Memphis, at this volleyball tournament. For the first time in probably 30 years, I’m singing “The Star Spangled Banner” again. It’s not because America is now a shining light in the world; in fact, it’s the exact opposite.

But I finally listened — really listened — to the song’s lyrics and their underlying significance, and that changed everything.

The anthem we sing here in the U.S. is actually just the first stanza of a four-stanza poem written by Frances Scott Key. It starts with a long question:

O say can you see, by the dawn's early light,

What so proudly we hail'd at the twilight's last gleaming,

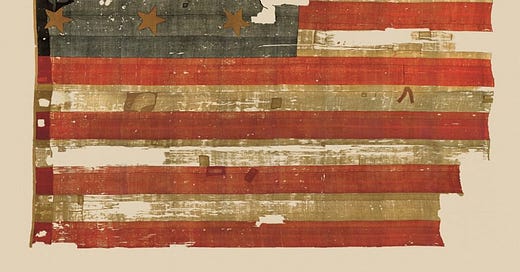

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O'er the ramparts we watch'd were so gallantly streaming?

In four flowery, adverb-laden lines, it basically asks, “Is our flag still intact? Did we win or lose last night?” I’m not knocking the quality of poetry — it’s a lovely example of its time period. (And for more on the battle that inspired the poem, click here.)

But then, in the next two lines, it answers its own question:

And the rocket's red glare, the bomb bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there…

Okay! you might think, question answered. The flag is flying. We’re done here!

Generally, if you pose a question in a poem or song or essay, you don’t just answer it in the very next line. It tends to shut down the whole experience, if you will, of the journey.

But that’s what Key does. And then he asks again,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

Why would he do that?

In all those years of not singing it — and even of singing it — I never once noticed the structure of the anthem or considered the implications of it. Frankly, I didn’t pay that much attention. I just mindlessly warbled or protested mutely, depending on the decade.

I do realize now that its structure — question, answer, question again — is what made it difficult to commit to memory when I was young, because it’s nonstandard. That’s not how most stories are told.

And yes, I know Key wrote three more stanzas to the poem, which makes the first stanza just an introduction to the whole piece. But I think Key had a very specific reason for answering the posed question so early in the game, and then restating the question.

Before I lay that out, keep in mind also that this first stanza, and only this first stanza, was chosen to be our national anthem. After living through the past three years, I think that was completely intentional.

The anthem lands on me now in a way it never did before, because it ends with a question, not a benediction like “God save the King,” or a declarative statement like “O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.” That may seem trivial — so what if it ends in a question? For me, it’s a revelation.

Ending the song by asking, again, “does that flag still wave over the land of the free?” is not just a lyrical flourish or a rhetorical question; it’s a call to action. It’s a message in a bottle, heaved into the sea of tomorrows in the hope that future U.S. citizens will heed that call.

It may seem like the whole anthem is about the flag, but it’s not. The title, “The Star Spangled Banner,” didn’t emerge until much later. Key called the original poem “The Defence of Fort M’Henry,” because he wanted to elucidate and honor everything that flag is waving over, not the flag itself. The banner is just a poetic prop, a symbolic stand-in for the true object of reverent focus: the rights colonialists gave their lives attempting to defend.

The poem is essentially asking, “Hey Americans in perpetuity, are you watching to make sure that what we fought and died for is still relevant? Is America still a refuge for brave citizens? Are its people still free?”

Our anthem is a plea for vigilance, for attention, for active care.

At least this is how I’m choosing to interpret it, and this is why, after boycotting it for years, I’m singing it again.

I’m singing it to remind myself of what this place was founded for, what it was intended to be.

I’m singing it because the Constitution is something no other nation on this earth has, and good people, possibly our best people, died for it.

I’m singing it for whistleblowers and censored journalists and de-licensed doctors and suing-to-get-their-jobs-back health care practitioners, the brave people for whom this country should be a haven of freedom, not a source of intimidation.

Now, every time I sing “The Star Spangled Banner,” I’m answering the question, “does it yet wave?” by giving voice to my faithful heart: “no, it doesn’t right now… but someday, it will again.”

This is wonderful Mary! I too was ashamed to be British for many years, in light of many things 'our nation' did. But then I realised that Britain - and America - are not synonymous with the scumbags who carry out atrocities in the name of the people they are supposed to represent. The American people did not murder tens of thousands of Iraqis. A rabble who have siezed the institutions did.

I salute the good people of America, of China, of England, of Afganistan. I contest those corrupt monsters who claim to act on their behalf.

The idea that any kind of national pride is red-necked and regressive is poisonous propoganda from those who strive instead for an authoritarian world government.

Pride in our national culture and uniqueness is a good thing. I will salute your flag as well as my own.

And another thought - 'Lawyer Lisa' finished her substack post today with this:

"The fat lady is on our side. And she will not sing until we win".

XOX

Mary, thank you for this insightful reflection that only you could write!

Your mindful meditation on our national symbol is a reframe that is essential for us in realizing the beautiful future our hearts know is possible. As long as we remain trapped in duality, thinking our only choice is to either mindlessly sing along or remain mute in protest, we cannot create a better country.

The repeated questions of the anthem make it relevant for self examination in every generation, and you articulate it so beautifully as metaphor:

“It’s a message in a bottle, heaved into the sea of tomorrows in the hope that future U.S. citizens will heed that call.”

Yes!! Each of us in each generation has infinite potential to heed the call of creating a better future. What will we create?