Years ago, I worked at a small market research company located in a Midtown residential apartment on Manhattan’s East Side. My boss lived in the apartment, which made things weird at times, like when he’d emerge dripping wet from his bedroom with only a towel around his waist to tell me to print out the MetLife report and put it on his desk.

The other weirdness was that he called himself a vegan, which I accepted, since as far as I could tell, he pretty much subsisted on lentils, peanut M&Ms, black coffee, and whiskey. (At the time, I didn’t consider that milk chocolate wasn’t actually vegan.) His eating habits were odd, and didn’t seem particularly healthful, but who was I to judge?

By the time I started that job, I’d been a pescatarian for a few years — though that word hadn’t reached the vernacular yet — for two reasons: 1) for the health benefits, ostensibly; and 2) because I knew I couldn’t personally kill anything but a fish.

I say “ostensibly,” because in reality, my diet was driven by (and masked) a lingering food obsession — the last vestiges of an eating disorder that had started in college.

That obsession dwindled throughout my twenties as I cleared up other issues, and finally petered out altogether when I was pregnant at 31. Suddenly, eating was a matter of survival, not just for me but for another being. Motherhood nudged me into a new relationship to eating, one that centered on “how does this food make me feel?” versus “what is the ‘right’ way to eat?”

I’ve never written publicly about food before, I’m not a “licensed nutritionist,” and the topic of food is impossibly vast, but I feel compelled to offer a few things based on my experience with the healing capacity of food — take ‘em or leave ‘em.

Plus, I’m fed up (ha) with food becoming yet another battleground. Aren’t we divided enough?

We’ve all heard the quote attributed to Hippocrates, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.”

It seems that he didn’t say exactly that, but it’s a handy paraphrase of another statement he did say, which reads: “In food excellent medicine can be found, in food bad medicine can be found; good and bad are relative.”

Restated simply: some foods can cure you, some can make you sicker, and ultimately, it depends on the person and the circumstances.

Some might read that and think, “Thanks, Hippocrates, for this wishy-washy relativity. What’s the point of bringing it up at all?”

Here’s one reason why.

I’ve briefly mentioned my mother’s experience with cancer before, which started when I was in my late teens and ended when I reached my early twenties, but I’ve never talked about how it opened me up to a world of food-as-healing.

In my Midwestern house in the 70s, dinner plates held meat and potatoes, primarily, along with iceberg lettuce salads and some dejected-looking boiled frozen vegetables. I still can’t look at a lima bean without shuddering.

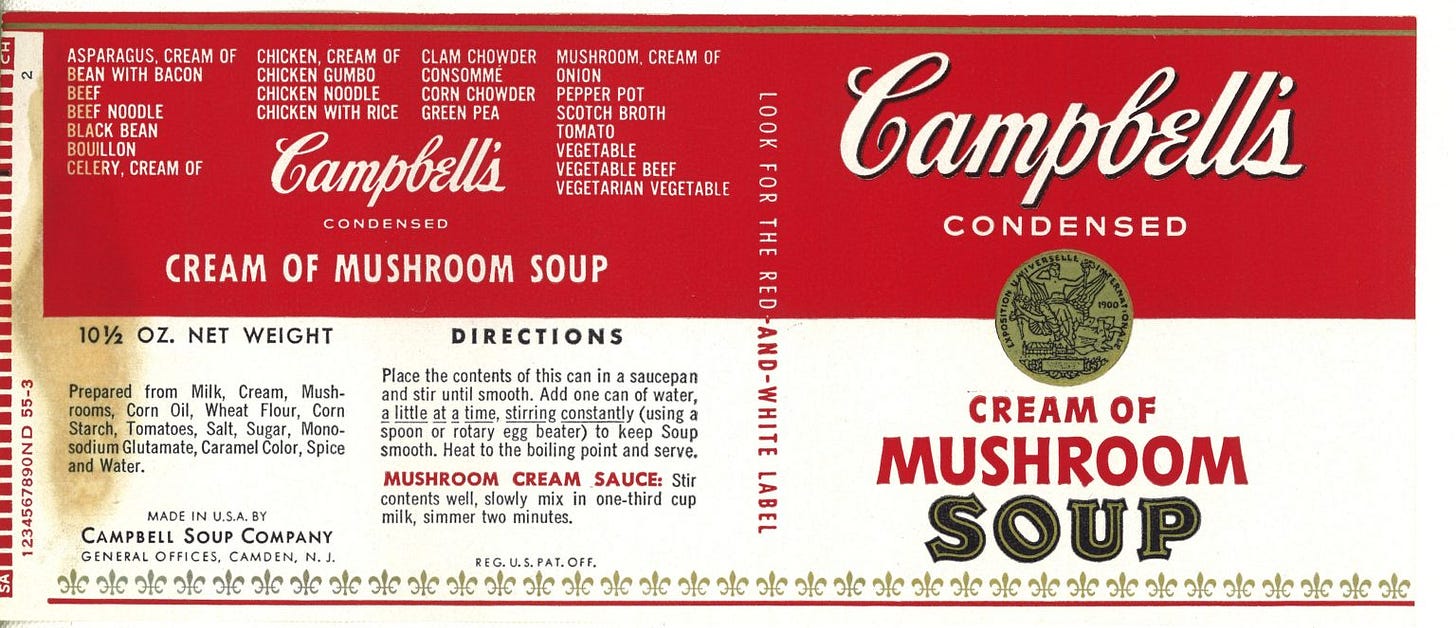

Casseroles were king, Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom Soup was a pantry staple, and The Joy of Cooking reigned supreme. No one was juicing vegetables, tofu had not been discovered, and brown rice was suspect — at least in Cleveland, Ohio.

My mom’s story is not a happy one, though I believe it could have been. She learned early on that my sister’s mother-in-law had healed herself of breast cancer in the 60s by using completely non-traditional methods (a version of Gerson’s juicing therapy, plus iridology).

Despite knowledge of this impressive accomplishment, and the how-to information provided by my sister, my parents did what they had been taught to do all their lives: they placed their faith in Western doctors.

Sure, the salads went from iceberg to romaine, and vegetables were more fresh than frozen, but these changes were window-dressing. We all watched as my mom grew weaker and weaker through multiple rounds of chemotherapy and repeated surgeries.

By the time she was willing to try a more unconventional route, it was too late. She died three and a half years after her diagnosis.

Her death felt, to me, preventable. Whether that’s true or not, I’ll never know. But it seeded a possibility of healing outside mainstream dogma, one which has continued to flower and bear fruits for me and my family — including an awakened understanding of the power of food.

Just like freedom is an art, healing is an art, and eating is, too. We all know that what works for one person doesn’t necessarily work for everyone. My sister’s mother-in-law cured her cancer with juices. My daughter cured her Lyme with a total plant-based detox diet.

, a wonderful vegan chef, has kept MS in check on a vegan diet.Yet Jordan Peterson cured his fatigue and depression on a carnivore diet, ditto Celia Farber. A quick search reveals countless YouTubers telling their own stories of curing their autoimmune diseases by eating only meat.

Vegan? Paleo? Keto? Lion? Omnivore? The answer will always be: it depends.

What are you trying to achieve? Are you looking for healing? Is your illness acute or chronic? How old are you? Are you breastfeeding? What kind of work do you do? Do you live in a warm or cold climate? Is it summer or winter? Where are your ancestors from?

Then there’s the food itself: what is the quality of it; where and how was it grown? Factory farmed or biodynamic? Was it processed? Is it canned, frozen, cooked? If it was an animal, what kind of life did it have? What kind of death did it have? I could go on and on.

Which levels me up to the spiritual aspects of food — the place most people don’t go when they’re debating the merits of one diet over another, except for those who choose veganism for moral/ethical reasons. (Not every vegan does.)

Plenty of diets have spiritual underpinnings; Hindu and Buddhist vegetarianism come to mind. I want to look briefly at the macrobiotic tradition, based loosely on Zen Buddhism and the traditional Japanese diet, because I think its nutritional philosophy offers some fascinating insights into our times.

In macrobiotics, all food is on an opposing but interconnected yin/yang energy spectrum. On one side is yin, considered to be classically feminine, cool, and “expansive in nature.” It includes sugar, alcohol, fruit, and vegetables. If meditation, spiritual insights, and exploring realms of higher consciousness are your jam, then macrobiotics says eating more yin foods will help take you there.

At the other extreme, yang is considered masculine, warm, and “contractive,” and includes meat, fish, eggs, salt, and cheese. Yang foods are good for grounding, bringing someone into the “real world,” physical activity, competitiveness, and a focused mindset. It’s great “battle food.”

Macrobiotics teaches that happiness and health reside in the balance. If you are “too yin” — scattered, tired, spaced out, unmotivated, anxious, or overly sensitive — you might need to add more yang foods to your diet. Conversely, if you’re tense and angry, picking fights out of excessive aggression, you may want to lay off the meat.

My former boss may have actually achieved some sort of middle-of-the-road congruence with his “vegan” diet, since he was essentially eating at the extremes of both yin (whiskey, sugar) and yang (coffee, nuts), with the mainstay of neutral lentils at the center.

I was interested to learn that EMFs, toxins, and stress are all yin-inducing. Might the prevalence of all three be contributing to the carnivore diet’s surging popularity, as an unconscious drive to restore balance? Veganism has been on the rise as well; could it be a balancing response to decades of warmongering? Could both be true, simultaneously? I believe they could.

I will say that my experience with diets at the extremes — raw food, my daughter’s highly restrictive detox, Gerson’s juicing protocol — has convinced me that they are extraordinarily healing… but only for a limited amount of time.

I think of them as extreme measures to be used in cases of extreme illness, not as sustainable lifestyles, and I wonder if the same will be true for all-meat diets. They clearly have healing properties as well, and they are certainly just as extreme. What will be their long-term effects?

And how is it that two diets that are diametrically opposed to each other could each have such healing capabilities? What do they share in common?

Well, there’s the obvious: extremism. All extremism is marked by singleminded and passionate belief in the ideology involved. Belief has been proven to have immensely powerful, inexplicable effects on healing that we are only recently beginning to understand, thanks to people like Joe Dispenza and Bruce Lipton.

Studies like the Milkshake Study back them up: when participants thought the shake they were drinking was “indulgent” (620 calories), their bodies responded with making more ghrelin, the “I’m satisfied” gut peptide, whereas participants who believed the shake was “sensible” (140 calories) produced far less.

Same shake, different labels, markedly different bodily outcomes. What are we do make of this? And what about all those people I listed above, the ones who healed themselves of various ailments? Were they able to do that because they believed that [insert food category here] would heal them… and so it did?

And what about my mother? As I come to this point in my writing, I realize that even if she had decided to change up her diet completely, it might not have had the same healing power for her that it had for my sister’s mother-in-law, because my mom’s belief system was completely different. Her faith lay elsewhere, not in nutrition.

And then I think… oh lord, did introducing doubt in Western medicine doom her? and I decide that I need to let it go. Her path was her path.

I turn back to the question posed above: What do extreme healing diets share in common?

Annemarie Colbin, author of Food and Healing, likened quantum physics to food. She said that just as light can be both a particle and a wave depending on the circumstances, a carrot can be both as well: particles correspond to all the nutrients in a carrot, the “parts” like fiber, Vitamin A, and water; waves correspond to the relationship that exists between all those parts and include flavor, color, and crunch.

I’ll take it a step further. I think that the wave component of a carrot is also the vibrational energy, the life force bestowed by water and beamed from the sun, that cannot be seen or quantified. It’s the indefinable, intangible animation that infuses vibrancy and even identity into the carrot; it’s what makes a carrot a carrot.

In the case of an animal, a chicken, say… the wave component is made up of that same vibrational energy, but in this case it’s not just the life force of food and water she eats that affects it, but it’s the quality of her life, her interactions with the world around her that make her either calm and peaceful, or panicked and fearful.

The parts of any object — the measurable components — may be stable, but the waves are always changing. And the waves that vibrate at the highest frequency, the ones that have the most healing potential, I believe, occur in and are fostered by Nature.

Both the carnivore diet and a Gerson-type diet stress the importance of “clean” foods, consciously raised and grown in harmony with Nature: organic, pesticide-free, non-GMO, no antibiotics, free-range, local. (It’s interesting to me that what they have in common is a reverence for the Earth, whether they realize it or not.)

Their “parts” are completely opposite, but their wave components are the same: they’re high in the vibratory energy necessary to assist the body’s innate ability to revive. In contrast, processed foods — animal or plant — have little in the way of healing power, given their distance from Nature (lab-grown meat, I’m looking at you).

I think this is why both diets have such significant success rates; they’re characterized by strong, focused belief and elevated energetic resonance.

I’m sure some have articulated a similar theory, and other theories as well. All any of us has is theories, because when you get right down to it, we know almost nothing about food. It is as complex as Nature itself, as impressionable as humanity itself, and as inexplicable as the divine itself.

Which brings me back to why I wanted to write this essay in the first place.

With all of the known and unknown variables that are at play when we talk, think, and argue about food — how can anyone tell anyone else that their way of eating is right or wrong, better or worse?

Except for the processed food part, of course. 😉

Not long ago, what you ate was pretty much your own business, like what kind of sexual acts you enjoyed or whom you voted for. Now, in this relatively recent lookatme! culture, people share all sorts of personal information about themselves, which isn’t in itself a bad thing. What I question is the escalation of personal choice to moral and political stridency.

(I have to pause here to acknowledge that abortion is a topic that certainly fits that category, and that I respect all opinions on it. I’m not able or willing at the moment to take it up, but may in the future.)

Does food have to be emotionally charged, too? Can’t we all just eat whatever the hell we want and get on with it?

Is it just me, or is the list of “controversial” topics getting longer, quickly? Some have been around for ages: party affiliation, abortion, gun rights, race... but issues like gender, immigration, vaccination, climate change, freedom of speech, views on voting fraud… those feel more recent, and more vitriolic.

And now food.

Food extremism, like all extremism, is handy for political agendas. It’s not just another way to splinter us off from one another, it may be the most effective way. Think about it. Other than water and air, is there anything that unites us as a species more than food?

In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said:

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.”

I realize that the concept of “sitting down together at a table” is metaphorical, but it originates in the image of communal nourishment, in some kind of basic acceptance of one another despite what feel like insurmountable differences.

When our beliefs about food become fervent, zealous, and messianic, I think of them as “foodogma.” Foodogma prevents us from recognizing the possibility that what works for us may not work for others, and it locks us into a rigid mindset that may not serve our own well-being over time. Foodogma runs completely counter to Hippocrates’s wisdom. Here it is again:

“In food excellent medicine can be found, in food bad medicine can be found; good and bad are relative.”

In food, as in all of human existence, there are no absolutes, no one-size-fits-all solutions. We’ve all heard about the guy who smoked every day and lived to be 100, and the health nut who dropped dead at 50. My boss called himself a vegan and ate M&Ms, and although he often pulled out his own eyebrows, he seemed pretty content. And according to LinkedIn, he’s still kickin’.

Look, I talk a big game about processed foods, and I do try to avoid them, but you’ll still find canned beans, canned diced tomatoes, and yes, even boxes of mac-n-cheese in my cupboards. Given my personal food history, I’ve found that not being rabid about what I eat is actually healthier, for me.

In that spirit, I encourage you to free yourself from foodogma, and eat what makes you healthier — with gratitude for the absolute blessing of sufficient sustenance. Try out carnivore. Try out veganism. Try eating mainly unprocessed foods. Then listen to what your body is telling you — because it knows — and decide what’s best for you.

Then pull up a chair, take your [insert favorite food] out of your brown bag, and join me and the rest of humanity at Mother Earth’s table as we “break bread” together. Remember: in a food war, as in all wars, the only winners are the architects.

Bon appétit.

Great topic Mary! I've been gradually coming to the conclusion that most of us suffer from 'low grade food disorders'. I start from myself with that of course - never been underweight nor overweight, but can certainly under certain stress conditions be susceptible to bouts of 'food abuse' of varying intensities. When the food disorder is 'low grade', I think it goes unnoticed for decades. I also work pretty hard to stay fit and healthy and have tried many of the 'systems', including a several years of 'almost' vegarianism (quite a long time ago, and 'almost' cos I allowed myself a piece of fish or chicken every couple of weeks or so), and more recently the new fad for keto, which I still do cyclically, and find really beneficial. Then I do off-cycles, and then sometimes the off-cycles degenerate a bit!

Certainly agree that personal choices are rapidly becoming moral obligations for the rest of the world to follow suit. Part of the state of 'mass psychosis' that is still sweeping the world. Those who eat meat (like me - since time has taught me that I flourish much better that way - even though I have reservations about the killing part - and especially the inhuman farming methods part) are becoming 'bad people', like all the other growing list of things for which some seek to make everybody except themselves 'the bad people').

What is 'healthy' definitely varies from individual to individual. And I increasingly think that just one's relationship to food - how much we eat, when, with what attitude, enjoying food etc, can make as much differnece as the WHAT that we put in our mouths. The most important part about the what, is 'keep it close to nature'. As a nutritionist on a video I watched awhile back said, 'vegan, paleo, keto, carnivore, they're all good, so long as you eat real food'.

As for lab-grown meat, seems to me that nobody with a trace of objectivity and intelligence can fail to have noticed that every time we move food further away from nature, the consequences are very negative. I'm looking at you 'philanthropaths'.

Food is a really big deal. Great that you that you have shone a light on it Mary! And I might dare to predict you'll get a big response on this one - it will touch a chord with a lot of people!

XOX

Thank you for bringing particles and waves of light to this complex and vital topic. Love the idea of opposing sides ultimately sitting down together at the table of harmony.