Motorcycle Insights

I went to motorcycle class to renew my license. Who knew I would come away with such a useful life lesson?

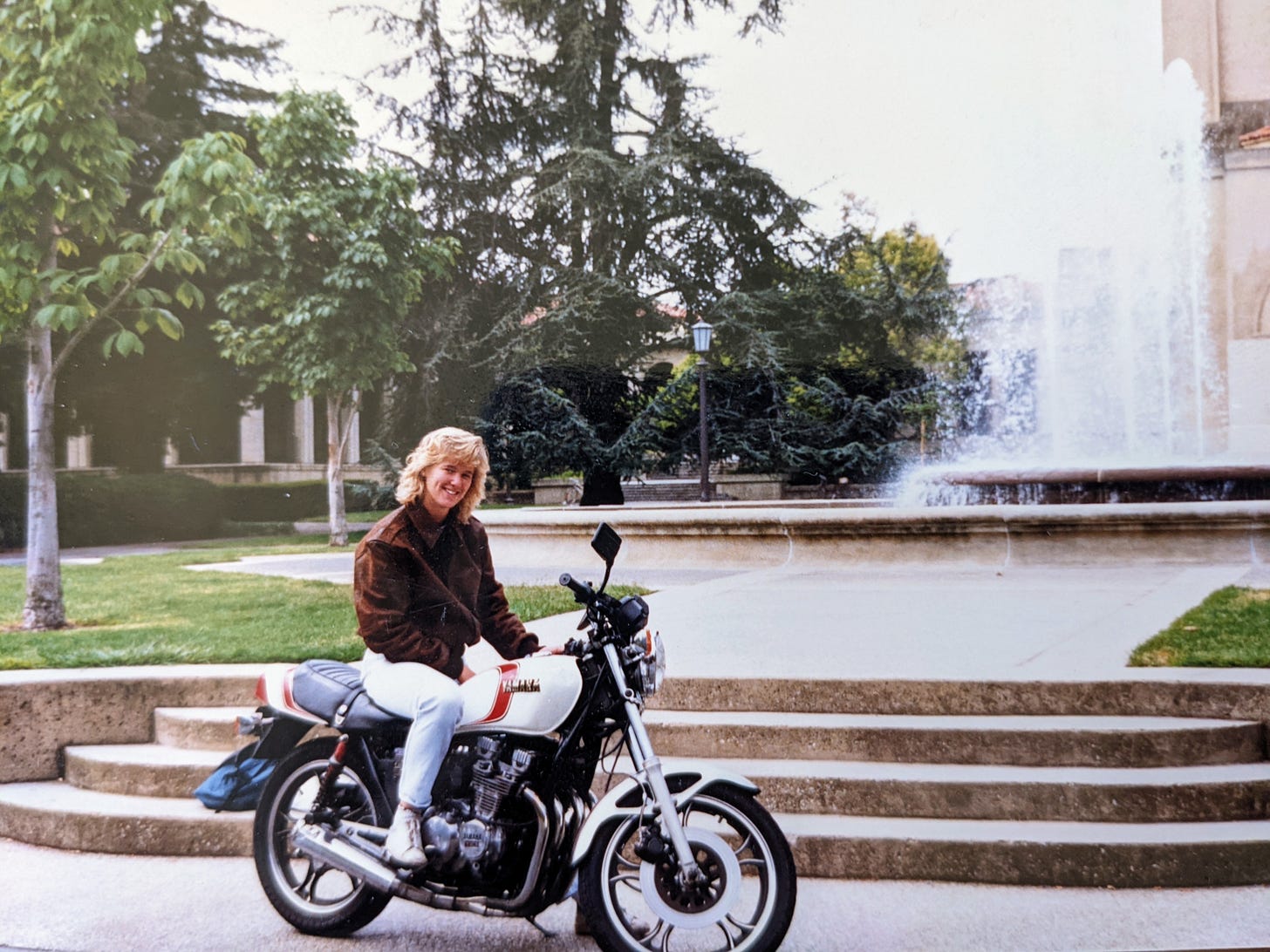

My junior year in college, fate delivered me a best friend in the guise of a randomly-selected roommate. Jen was a brilliant, creative, free-thinking bundle of energy and compassion, with a British accent and a buzz cut. (She is all of those things, still, though her hair has grown out.) She also knew how to ride a motorcycle.

When I mentioned I had always wanted to ride, she leapt on the idea. Within the week, I was following her in her car through the darkening hills of San Francisco as she rode my recently-purchased Yamaha Seca 550 slowly back to campus.

The next morning I awoke in a sweat. The used bike had a cracked airbox and I had no clue how to ride it. What had I done? What was I thinking? I spent a fortune on it! Perhaps I could re-sell it, and recoup my (now-laughable) $500 investment.

Jen was having none of that. “You’ll get the hang of it,” she said. I had my doubts. I suspected that her riding competence stemmed from her prodigious left-brain; wasn’t she a product design major? She laughed. “It’s not that difficult. Trust me.”

A few weeks and many parking-lot lessons later, I proved her right. It turned out that even an English major could learn how to ride a motorcycle.

My younger son Henry, now almost exactly the age I was when I bought that bike, came to me a month ago with sparkling eyes. “Mom! I signed up for a motorcycle safety course so I can get my license. Wanna do it with me?”

I paused. In the intervening 30 years since I had ridden my bike in California, I had moved to the East Coast and raised three kids, abandoning much of my former self — including my motorcycle license, which was one of the first things I jettisoned… with pangs of regret.

Now, my elder son was planning to ride across the country this summer and my younger had visions of a similar junket in Greece. Henry mistook my hesitation for reluctance and pressed. “It’ll be a bonding experience,” he said, knowing my weakness (I’ll call it a proclivity) for connection. I needed no more prodding. I went online and enrolled.

Which is how I ended up a few days ago on a large plain of asphalt, astride a tiny red and white Honda Grom 125, baking inside my borrowed helmet and rubber gardening gloves. No, there are no pictures.

There are, however, some unexpected takeaways. Here’s one.

My instructor for the course was a well-meaning corrections officer. (I’ll call him Mitch.) Tall and pasty, Mitch relied on the education-through-shouting style, perhaps conflating the ten of us with inmates. Any mistake we made elicited a punishing comment such as: “WHADJA DO THAT FOR? WHO THINKS ITS A GOOD IDEA TO PUT THE BIKE IN SECOND GEAR WHEN YOU’RE GOING ONE MILE AN HOUR?”

Demeaning though he was, he knew motorcycle safety inside and out, and he was determined to bulldoze that knowledge into us during our sweltering day and a half together. Once everyone could start, accelerate, turn, and stop with some proficiency, he huddled us up.

“ARIGHT, LISTEN UP. WHO HERE KNOWS WHAT TARGET FIXATION IS?”

All of us knew, having previously suffered the mandatory three-hour online course that drilled such terms. We waited politely for someone else’s regurgitation, which eventually came from me: “It’s staring at where you don’t want to go.”

Mitch blinked. I don’t think he’d ever heard that definition before. “Uh, okay,” he mumbled, then recovered. “IT’S FOCUSING ON A THING, A HAZARD, RIGHT? LOOKIN’ AT IT SO HARD THAT YA CRASH RIGHT INTO IT! RIGHT?”

Ten bulbous helmet-heads nodded.

Anyone who has ridden a bicycle has probably experienced target fixation. The one thing in your field of vision that you want to avoid — the pothole, the rock, a sudden squirrel — exerts a tractor-beam-like magnetism, pulling you directly into its path. It’s almost creepy.

Clearly, we are programmed to be attuned to anomalies, for evolutionary advantage: What’s that thing on the path? A snake? But that advantage was never designed for speed; it’s of benefit only to a walking — or even running — individual.

Cruising along at higher speeds flips that benefit upside down. Something designed to keep us safe CAN HAVE DISASTROUS CONSEQUENCES, as Mitch hollered at us.

There are a couple of takeaways from this. The first is so obvious, it’s a cliche. Yes, we all need to slow down in our lives enough to be able to react to sudden obstacles.

Okay, great. Moving on.

The other one relates to freedom — which is why I’m writing about it here. If you take the physical reality of target fixation and convert it to psychological metaphor, you might find, as I do, a valuable life lesson.

For years I’ve heard the statement, “What we pay attention to, grows.” It has always made sense to me. I’ve had friends who drew to them the very things they obsessively attempted to avoid: financial instability, isolation, illness. I’m not blaming them; many times they are just operating on the programs “installed” in the first seven years of their lives — as Dr. Bruce Lipton, the developmental biologist, describes in his fascinating research on epigenetics and human behavior.

Sometimes, though, the obsessive focus is more intentional — or it appears to be. I offer my own behavior as an example.

Over the past two years, before I started writing The Art of Freedom, I became more and more focused on the illness of the world. I read article after article about tyranny, oppression, censorship, malfeasance, corruption. I listened to podcasts and watched videos. It felt like my moral duty to be as informed as possible, so I drank it all in — starting as soon as my eyes opened in the morning, filling in the gaps in my day, and ending with a nightcap before sleep.

It felt like I could not get enough. I couldn’t look away.

It also felt like my inner world was darkening. Hope seemed harder and harder to locate. Cynicism was showing up instead. I found I couldn’t imagine a bright, beautiful future anymore, because target fixation had erased everything outside that narrow band of concentrated ugliness.

My dear college friend Jen and I often commiserated. What to do, in the face of all this doom? Her response was to pick up her spade and continue working with the land, transforming the acreage slowly into a sanctuary of regenerative, sustaining bounty and refuge. (More on Jen’s path in a subsequent essay.)

The antidote, for me, was to start writing this publication. I chose to pick up my pen, shift my direct gaze from the darkness, and write what I want to see, where I want the world to be: on the illuminated path to freedom.

It’s a conscious choice. Remember, we are programmed to keep our eyes trained on the hazard. Seated on my Grom, even at a measly 10 mph, I had to force myself to look away from the orange cones to execute a safe slalom through them. Over and over, the temptation to stare at them kept taking hold.

It helped to hear Mitch shouting from across the parking lot:

“TURN YOUR HEAD! LOOK WHERE YOU WANNA GO!”

He was right. When I allowed my peripheral vision to take care of the target, all of a sudden the path through the cones magically appeared. As I did the exercise over and over, I got better and better at it. I also remembered why I so loved riding my motorcycle.

Keep in mind, that was at a relatively low speed. God knows we are moving at light speed these days. So to carry the metaphor forward, that means the only way we will get better at riding the path of our choosing is to practice, over and over, looking toward the destination we most desire — in every realm of our lives, and in the smallest of ways.

What does that practice look like for me? How do I keep the target where it belongs, in the periphery?

I pay attention to my attention. I ask, is this thing (email blast, news event,

conversation) worth my attention and energy? If it isn’t, I move on. I read articles selectively. I follow the people who aren’t just trying to scare me.

I listen to those who offer and are actively working toward solutions. I write this newsletter and make sure I stay connected to Source.

I practice slowing down to observe and love the million tiny miracles in my

midst (a seed sprouts! a cake rises! dreams absorb me all night!). I keep doing what lights me up, like donning earbuds and dancing to music only I

can hear, or walking in the woods… or taking a motorcycle safety course to bond

with my son before he leaves for his junior year in college.

Making those choices helps keep me in balance as I navigate this crazy obstacle course called life. I’m not perfect at it. I still have days when current events pitch me off my ride and I end up tumbling down some dark rabbit hole. But now, thanks to Mitch, I know how to climb out and get back in motion: by looking where I wanna go. Soon after I learned to ride my Yamaha, Jen bought her own bike. Until recently, I didn’t understand why my fondest memories of college all seemed to include the two of us and our motorcycles: riding to Safeway at 3am for ice-cream sandwiches in the middle of an all-nighter; alternately laughing and whooping as Jen pushed me down an incline on my dead-battery bike to pop-start it so I could get to class on time; riding in tandem up into the foothills, the scent of eucalyptus all around us, to watch the sun set from the highest point.

Now I know. There is an unmistakeable aura around these events that glows bright as I look back. No one was telling us what to do or think. We had autonomy and sovereignty, and we were going where we wanted to go. Isn’t that the path of true freedom, for all of us? Isn’t that our birthright?

No wonder I yearn for a motorcycle again.

This happens in kayaking too. Do not look at that dangerous thing you’re trying to avoid!