I recently re-read the January 9 entry in Mark Nepo’s The Book of Awakening. In it, he relays the story of a friend transferring all his fish to a bathtub while he cleaned out their tank. The friend watched in astonishment as all of the fish clustered together at one end of the tub, rather than striking out and enjoying the freedom of a capacious tub, as he expected them to do.

The fish were so conditioned by the confines of their small tank, they didn’t even know it was possible to surpass the non-existent boundaries.

Nepo makes the following statement:

“Life in the tank made me think of how we are raised at home and in school… of being warned over and over that life outside the tank of our values is risky and dangerous. I began to see just how much we are taught as children to fear life outside the tank.”

We are, indeed. Even in ways we might never recognize.

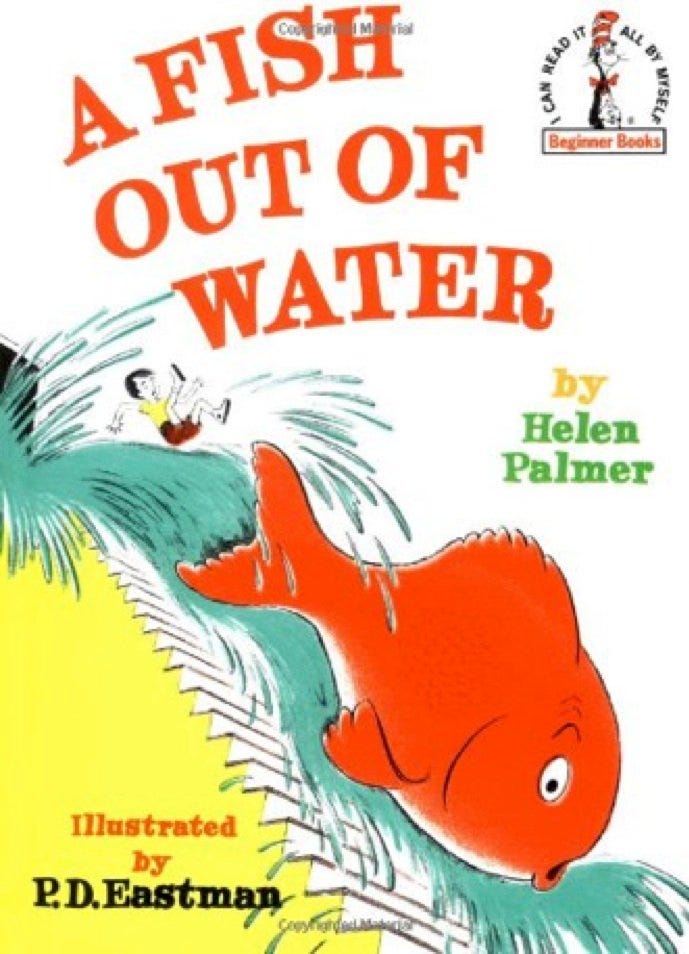

Take, for example, a short story by Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) called Gustav the Goldfish, which his wife Helen Palmer in 1961 turned into an easy-reader book called A Fish Out of Water. Illustrated by P.D. Eastman, the book bills itself as a cautionary tale on pet ownership: “a young boy hilariously learns the consequences of not following instructions.”

Quick synopsis: A boy buys a little fish from fishstore owner Mr. Carp, and names it Otto. Mr. Carp tells the boy to feed him only one little spot, but the boy gives him the whole box, and Otto soon grows to fill the entire fishbowl. Panicked, the boy puts him in successively larger containers – a flower vase, bigger pots, the bathtub – but Otto just keeps growing.

Eventually, Otto ends up in the public pool. The boy calls Mr. Carp, who shows up with flippers, a mask, and a black box. He dives in with the box, and disappears under the water.

Suddenly, he pops out of the water, holding a small fishbowl with a small Otto in it. No explanation, just from the author a breezy, “Mr. Carp had made him little again.” And then Mr. Carp says, “Don’t ask me how I did it. From now on, PLEASE, don’t feed him too much. Just so much, and no more.”

Cute story, except that it always nagged me that we were left with zero explication of how Otto transformed from ginormous to tiny again. That process was completely (and conveniently) obscured, a lazy authorial choice, IMHO. But I never dwelled on that; the story was sufficiently engaging for my little ones, and the illustrations were sweet.

As I’ve written before in this publication, stories help us make sense of the world. They show us how to be in the world. I believe they actually have the power to create our world.

I often deconstruct children’s stories, because their messages carry disproportionate power. Children unquestioningly absorb everything around them – and I mean everything. Images, sounds, words, even intentions and emotions: all of it bypasses critical thinking and heads straight for the deepest levels of their consciousness. This is one of the reasons my husband and I got rid of the television when our children were young. (Best thing we ever did as parents, and another topic for another day.)

I didn’t think much about the message of A Fish Out of Water until I came across the Nepo anecdote… and then it hit me. Charming though it is, A Fish Out of Water is also a useful teaching tool to keep us “in the tank.”

It starts with the book’s title and cover art. We all know, even at a young age, that being “a fish out of water” is a Very Bad Thing. Check out the fear in Otto’s eyes as he cascades down the stairs:

The message, before you even crack open the book, is: don’t leave your safe, comfortable environment.

Next come some ominous instructions, like a modern, kid-friendly version of the “whatever you do, don’t open the box” warning in Pandora’s Box. In this story, Mr. Carp warns the little boy: “something may happen – you never know what.”

Message? Do what I tell you, kid.

The rest of the book is devoted to reinforcing those two central messages, over and over. The police get involved! The fire department is called! Everyone in the pool (insert intense social disapproval here) hollers “you take that fish out of here!”

The pressure to do what he’s told builds, such that the kid ends the book by saying “Now, that is what I always do. Or something may happen… and now I know what,” which essentially translates to “I always do what I’m told by an authority because the alternative is HORRIBLE.”

But what, really, is the problem with Otto? One spot of food doesn’t cut it for him. The boy somehow senses this and wants to give Otto what will make him happy, so he feeds him more and Otto grows.

Why is that so awful? Because the tiny little fishbowl Otto was placed in by someone else doesn’t fit him anymore?

Hmmm.

I’m embarrassed to admit that only very recently did I realize that what I called houseplants were actually plants that did not belong in pots; they were plants that were living in the wrong climate.

I know, I know. An obscene omission in my education.

You’d think somewhere along the way I’d have clued in that all those “indoor plants” weren’t really meant to be indoor. I mean, really, what did I think? That on the 8th day God created a separate group of plants that couldn’t survive outside? Sheesh.

It took a trip to Mexico, where I recognized my 12-inch “houseplant” as a 12-foot tall tree, to slap me out of my tank-induced ignorance. It was a moment of pure astonishment and humility, one that provoked an unsettling question: what else have I taken at face value?

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not opposed to following directions. But why the mystery surrounding Mr. Carp’s admonition? Why not just tell the kid, if you feed your fish too much, he’ll grow too big and you won’t be able to keep him anymore? Isn’t it better to be transparent?

And who gets to decide how big Otto “should” be, anyway? Maybe, like my “houseplant,” he’s actually destined to roam the oceans with a pack of whales! Wouldn’t that be an interesting twist?

I’m reminded of the Garden of Eden story, as classically told: Adam and Eve eat an apple from the tree of knowledge and boom, they’re cast out of the garden. I can see the same metaphor playing out in this story, with fish food standing in for the apple (or vice-versa), and I have the same issue with it. Again, it reeks of “do what you’re told or BAD THINGS will happen.”

Speaking of food…

For human beings, there are many types of “food” beyond sustenance for physical survival. Food can come in the form of the arts, love, acceptance, intellectual stimulation, emotional support, spiritual connection, or some combination of all of those. Anything that nourishes us is food.

Imagine, if you will, that Otto is craving that kind of nourishment. For him, “one spot” is not enough. Ingesting the whole box is like kickstarting a soul expansion of some sort; without eating any more, Otto just keeps outgrowing his containers. His inner development switch has been flipped, a process that once started can never be stopped. Consciousness once raised can never be lowered, as they say.

Except in this case. Thanks to Mr. Carp and his mysterious black box, Otto is delivered back to “normal,” that is, small, captive, and powerless.

Society has always wanted to keep us small. We are more manageable that way, which is important because there are usually way more of us than them. Governments, religions and other ruling organizations have always operated on the understanding that the only way to keep us in check is to either scare us into compliance (Jail! Fines! Death!), or convince us that what they want us to do is really what we want to do ourselves.

And the earlier that convincing process starts, the better. Shoving full-grown adults back into tiny bowls is a lot harder that impeding young growth. If we all learn at a young age that defying authority leads to bad things, or that the version of reality we are fed is the only version there is, we will police ourselves. We will willingly stay within boundaries. We will “live small,” scaling down our hopes and dreams to fit within invisible walls of our own creation. We will hang out at the end of the tub, huddled together within imaginary borders whose existence we never think to question.

That’s why this innocuous children’s story alarms me so, particularly in light of the events of the past two years. It’s alarming to recognize the many ways we are taught, as Nepo says, “to fear life outside the tank.”

No, I don’t think Helen Palmer sat down to write this story, thinking, “Aha! I’ve got just the tale to perpetuate a docile, unquestioning society – starting with children!” But let’s not forget: she swam in the tank, too. It takes a certain kind of individual – I haven’t quite figured out the determining factors yet – to be able to actually see the tank that surrounds him or her.

And yet another kind to gather up the courage to swim beyond it.

During a recent kayak outing, I paused my paddling to drift on the calm saltwater, the sun beating down. All around me, periodically, I saw and heard the slap-splashes of fish. Why were they leaping, some of them multiple times in a row? A pragmatist might say: to eat an insect, or escape a predator.

To me, the dreamer, it looked like exuberance, a desire to fly above the tank, even if only for a moment. It looked like a hunger to leap out of one reality and into another, to be a fish out of water, witnessing the world just beyond its own, the other one that is always there, waiting.

So I ask you: what is your tank? And who is feeding you?

Well said, and I know that book!! Read it many times though missed the implications you've highlighted.

"Society has always wanted to keep us small." Indeed it do. Thanks, Mary.

Hi Mary, Your piece resonated for me with my drumming. Having attended many drum circles that inevitably devolve into a staccato thumping with all the spaces filled, and having studied African diaspora rhythms, what this culture sees as a drumming free-for-all, is in actuality a highly structured set of agreements from which infinite freedom and improvisation flows. So it is with many Native cultures rituals. Structure = Freedom.

Yay! I so enjoy how that informs your writing as well. Thank you.

Denni