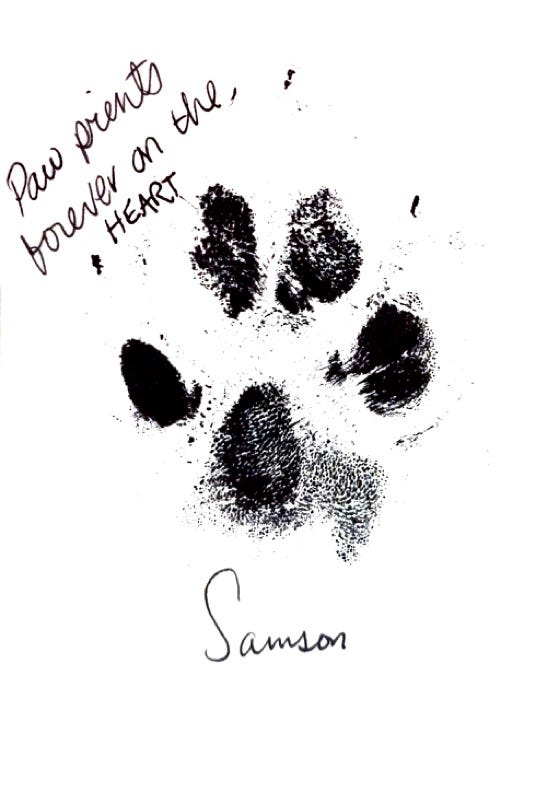

Samson

A Love that Rescues

Dear readers,

This is not the essay I expected to write as the first after my hiatus, but as a wise friend recently said to me, “what we need finds us.”

I hope you are finding that to be true for you, too.

It’s good to be back. xox M

The heaviness in my chest is gone, now. It’s been two and a half weeks since we had to put him down. The heaviness of loss that drew my face to the earth has lifted; so too, the corners of my mouth in constant free fall for days.

I’m good again. I’m joyful.

But that doesn’t mean I don’t still have pangs.

The house is eerily quiet. There is no heavy breathing, no clicking of nails on the wooden planks.

I cooked a chicken a few days ago to make soup, feeling utterly lonely in the kitchen for the first time in a dozen years. I separated out the bones, carefully reserving the skin and fat on a separate plate, even though I was fully aware there was no expectant, drooling mouth at my side, patiently waiting to receive it.

I walk past my closet time and again and gaze at its now-empty floor, sigh, and think: How is it that in 2011, there was no perceptible void in my life, in our family? The five of us, plus our two cats, an assortment of chickens, and a few fish, felt topped-up. We lacked nothing; our unit was complete.

And then in that year, the name Samson was spoken. Out of our youngest son Henry’s longing came an online search, an application, and this being. A rescue.

I was nervous about him. He was a little jumpy. He looked sad, sometimes, but having never had a dog, I didn’t know if his expression was actual sadness or just some version of resting dog-face.

When we took him for walks, he pulled on the leash, hard. So hard that my wrist grew sore, so hard that he dragged our skinny little Henry face-first through the snow.

He busted through the electric fence in pursuit of a fox and ended up on the centerline of a 55mph country road.

I wasn’t sure about Samson. His gaze always pulled away when our faces got close. His teeth loomed large and beast-like, and he displayed them while panting — totally normal, but a clear departure from the animal behavior and physiognomy I understood, having grown up with only cats.

There was an eagerness to him, magnified by his (to me) oversized presence, that scared me a little. Why did he “mouth” my hand? Was he just evaluating it, probing for soft fleshy bits, waiting for the right moment to sink those big canines into me? Why had we invited this wolf-descendent into our home? Weren’t we happy enough without him?

An animal intuitive told us that he was jumpy because he thought we would get rid of him as everyone else had: his original owner, the shelter down south, the shelter up north, and his foster family.

She said he was insecure, worried about abandonment.

Of course, I thought. I’d feel that way, too. He just needs to know that we love him. That he’s safe. That he’s our forever dog. That we’ll never get rid of him.

So even though I had my doubts, that’s what I told him out loud to his furry, shy face, and internally, to his eternal dog-spirit: You’re safe. You’re ours. You’re home.

Everything changed after that, swiftly and miraculously. He stopped jumping up on us and on visitors. Yes, he still shook and trembled in the back of the car when we took him places, thinking maybe he was being handed off to someone else again, but even that went away in time. He calmed down.

He graduated with honors (not really; peeing on the mirror ruined his GPA) from Eagle Ridge, where his true diploma was a bestie-bond forged with my husband Peter — another being whose great fear was abandonment.

Together, they gave each other trust, safety, and love.

Sam graced the annual Christmas cards and yearly calendars. We took him everywhere with us, including Massachusetts, where he charmed Pete’s dog-wary mother with his sweetness, maneuvering his way into sleeping in her bedroom.

We inexplicably endowed him with a snarky, sassy voice and a lisp, voicing impertinent things like “perhapth now is a good time for my litht of grievantheth?” such that his personality grew and sharpened. He became an opinionated, outspoken, hilarious, and indispensable member of the McLaughlin family.

He was safe. He was ours. He was home.

He became an outsized character, an oversized presence… and there’s no doubt that the emptiness I feel at his passing is because I miss all of that, all of him. There is a void now, where there was none in 2011.

But there’s more going on here, which is why I decided to write this essay.

I noticed, almost immediately after his passing, that Samson had filled lots of unspoken needs, and some spoken ones, too: companionship, familiarity, comfort, loyalty.

But the deepest one he filled for me, the one we all have, whether we articulate it or not, was to feel loved. Samson loved, all the time. He loved us, the cats, the UPS man, even the melancholy teen girls dressed in black who came to our house for cast parties — them especially. They draped themselves over him as he sat on their laps for hours, furring up their spandex and reluctantly getting up to leave only when their rides came.

Sam was love. From what I now know about dogs, that is just what they are, what they do.

I mattered to him. Yes, I mattered especially at mealtime, but still… he was always, always, always happy to see me, and he showed it. After he was gone, I came home and there was no one to greet me at the door, tail wagging. I burst into tears. Clearly, to feel loved, to feel the happiness of another being to see me, to be with me, is huge.

It’s why mothering, despite all its challenges and sacrifice, was always so profoundly nourishing. My children were (almost) always happy to see me, too.

It’s why I’ve struggled with my husband’s sometimes tunnel-vision focus, why I once asked him to smile when he sees me walk into the room.

It’s why I’ve placed so much attention on an inner journey, on the path of connecting with Source; I’ve known instinctively that cultivating a relationship with the Love that is always present, always happy to see me, is essential to my inner stability.

Losing Sam, feeling the void of his absence, made me think at first that there is more work to be done in that arena, and there’s some truth to that. But I don’t want to call it “work” anymore. Feeling his loss has helped me rename it as “remembrance.”

I, like Sam, like you, like all of us, came into this world as a beam of freely embodied love. Over time, we forget that essential truth, paving it over with intellect, ego, social conditioning, and fear. As Wordsworth so beautifully put it,

“Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come”

We require great spiritual teachers to gently remind us: we are already love, already free. Samson did that for me. Yes, that means I’m putting my dog in the category of “great spiritual teacher.” I’m okay with that.

So here’s a poem of gratitude for my teacher:

Rescue

Such a love.

Such a love you were,

such a love you gave

Such a love for a boy who

wanted a dog,

who didn’t have his own

until the day you arrived

with your fear of guns,

swimming,

abandonment

Such a love that taught us all

what love was,

what love could be

Silly us, we thought we

were rescuing you

Such a love you called forth

in a man who needed it,

a man who’d never felt

that kind of patience,

that kind of wagging-tail forgiveness,

that kind of blind acceptance

to faults, mistakes, flaws

You loved him,

you loved all of us

with fish breath

and a muddy snout,

with stolen, buried mittens

and the sweetest brown eyes

that could not meet our own

You rolled over onto your back,

offering your belly to rub

like a happy buddha,

coaxing us into loving more,

loving better

The more we love,

the more we grieve;

the more we grieve,

the more we love

There is no other way

in this life

And there is no word yet

for the alchemy of grief, how

the perfection of pain,

the grace of goodbye

can become happy tears,

a living gratitude,

that comes and sits

in our laps

and stays as long

as we are willing to hold

such a love as this,

a love that rescues

I recently discovered this cartoon I had cut out from The New Yorker decades before Samson came into our lives, back when I thought we were complete without him:

In the end, Peter and Sam walked together, the two besties. Pete held his muzzle and looked deep into those eyes that had always wanted to look away. This time, they did not. And then, they closed forever.

One week — to the very day — before Sam died, Peter and I had walked over an abandoned bridge in North Carolina that volunteers have transformed into a magnificent garden. It’s called the Flowering Bridge, and it’s a marvel.

While I lingered over color and fragrance, Pete moved ahead. Eventually, he returned with a peaceful urgency. “You have to see this,” he said, taking my hand.

Hidden past the Friendship Garden, the Mirror Garden, and the Songbird Pollinator Garden, was the Dog Garden, created by dog lovers for dog lovers and their dogs. It’s a sweet place, with a stick-lending “library,” dog topiary, dogwoods, and the like. I thought it was cute.

Then I saw the bridge.

At the center of the garden, near the river, stands a “Rainbow Bridge,” its sides embracing hundreds and hundreds of dog collars.

How to describe the feeling of seeing this? Tears welled, not in pain, but in an unexpected tsunami of the purest love which rolled over me in waves: from all those grieving individuals who clipped a collar on the bridge; from all the dogs who adored those people; from all the volunteers who carefully crafted this place of beauty; from all the witnesses like me who stood in awe of that beauty and offered their own prayers of love.

I remember thinking, Pete and I will take Sam’s collar and clip it to the bridge someday. That word someday floated out in front, comforting me in its indeterminateness. Not today. Not this week. Not for a moment did I imagine that I had already rubbed his belly for the last time.

Grief felt for any loved one unites us all. “The mortar of our mortality,” as Unitarian minister Forrest Church used to call it. It also deepens us, if we allow it, pressing out more space in the clay of our vessel-being, so that we can hold more, feel more, love more.

The irony here is, we lack nothing. Love, as they say, is an inside job — it pours from Source, all the time, filling us up. Yet how much more love can we give?

The answer, as Sam taught us, is more, and more again. There is always more.

Such a beautiful written encapsulation of your grief alchemy, Mary. I'm so sorry for your loss and so grateful you got to experience such an abundance of love from Samson. 💙

Amother deeply beautiful and

moving essay, Mary. I am sorry for your loss, and moved by all that you gained.