I hated history in high school. Loathed it. U.S. history, European history, you name it. As soon as I cracked open the tome in front of me and started reading, my eyes would blur and I’d immediately want to either take a nap or eat more honey-roasted peanuts.

I dutifully committed to short-term memory all the state-sanctioned textbook dates and “important facts” of events like the U.S. Civil War or the French Revolution, then spit them all out on multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank tests to the satisfaction of my teachers, usually well enough to squeak out a decent grade. Within days of those tests, all of the information — really, every iota — drained out of my head like sewage down a pipe.

In college, I had to take a political science course to fulfill a graduation requirement, so I signed up for something called Arms Control and Disarmament. I sat in the last row.

The professor, a “famous” dude who formerly worked high up in government, tossed off names of historical events casually and repeatedly, while students’ heads nodded in smug, knowing concert: ah yes, the Bay of Pigs. Mm hm, Gulf of Tonkin.

I took notes so hard my hand cramped up after the 50 minutes was up. I shook out my fingers all the way from that last row to the registrar, where I changed my status in the class from “graded” to “pass/fail.”

I felt like an absolute idiot. I didn’t know anything about any of this, and to be perfectly honest, I didn’t want to know. I was happy that way. Who cared about this stuff, other than history majors? How was it relevant AT ALL in my life?

I did what I could to educate myself sufficiently to scrawl some half-assed essay in a bluebook at the end of the semester about the state of nuclear armament in the 80s. Apparently, it was coherent enough for a passing grade, but again, don’t ask me one single thing about the class.

So when my husband Peter and I recently drove past a sign along Route 75 for Athens, TN and he said brightly, “Hey! Do you want to stop there and check it out? Do you remember the story I told you about the Battle of Athens?” I paused, searching for a more diplomatic answer than “I’d rather eat tar, and no, I don’t remember.”

Pete is an avid historian — particularly of battles — so he’s regaled me with LOTS of stories of military skirmishes, large and small, over almost three decades. In fact, during the early years of our marriage, I would sometimes ask him to tell me about a little-known battle to help me fall asleep at night.

Imagine his surprise this time when he started to relay the set-up to the Battle of Athens —“During World War II, there was this corrupt official in Athens who was terrorizing citizens and rigging elections” and I stopped him with:

“Wait. Yes. I do want to go there. Let’s go.”

There’s a very good reason I remembered the story: it is relevant, almost ridiculously relevant, to my life and the lives of all Americans, frankly. As clueless as I was in high school history classes, I KNOW no teacher ever taught me about it, or even mentioned it. Now I know why.

Peter and I drove into the center of town, a tidy but beleaguered place among the ridges and hills of Eastern Tennessee. Bright sun illuminated almost empty streets. There were precious few shoppers, and even fewer shops to patronize.

We walked together in the chilly March air, certain that we would easily stumble across evidence of the battle in such a tiny town. Soon though, we became more and more puzzled at the lack of signage or any hoopla whatsoever; where was the self-guided tour? Where were the monuments? The plaques?

We eventually found ourselves stalled in front of a shop, debating whether to keep wandering around randomly or go in and ask. A pleasant woman appeared. “Can I help you folks?”

“Actually, yes…” I said, and Peter chimed in, “We’re looking for the old jail, the site of the battle.”

Her face registered something, but I didn’t know what. “Why doncha come on in, I’ve got a town map.”

As we followed her to the back of what turned out to be a lovely store, I said, “It’s so funny… we thought we’d be able to find things on our own. Why aren’t there any signs pointing toward some landmarks?”

She stopped, turned toward us, and her eyes swept the store, clearly scanning for other customers. The place was empty. Her face was again registering something, but this time it was unmistakeable: apprehension, slight but real.

“I just… uh, need to make sure…” She let that sentence drop as she stepped behind a counter and produced a small printed piece of paper. “So. Here’s a map.”

She busied herself with showing us where we were, and then a man appeared, just as she said, “There’s a book you might be interested in, I think there’s one in the back…” Her voice drifted off as she disappeared behind us to look for it.

The man picked up the thread she dropped. “People don’t like to talk about it much ‘round here. It’s a friendly town, and people want to keep it that way.”

I felt like I had stepped into a mini-series. I’m not used to dialogue like that, except in fiction.

This nice man then launched into an explanation of why no one wanted to talk about what happened on August 1, 1946, and I was riveted. All of a sudden, history mattered.

If you, like me, knew nothing about The Battle of Athens, well… sit back and enjoy. I think you’ll find the story quite a treat.

Most of what I’m going to relay comes from a recently-published book (2020) called The Fighting Bunch, by Chris DeRose. Unless otherwise stated, all the quotes come from the book. I don’t know if this book was what the pleasant woman went searching for at the back of her store, because she returned empty-handed. But it’s an impressive account of the events on and leading up to that day in 1946. As the book jacket states,

“For the past seven decades, the participants of the “Battle of Ballots and Bullets” and their families kept silent about that conflict. Now… after years of research including conducting exclusive interviews with the remaining witnesses and reviewing archival radio broadcast and interview tapes, scrapbooks, letters, and diaries, Chris DeRose has reconstructed one of the great untold stories in American history.”

After reading it, I understand now why it’s been untold, and why the pleasant woman was apprehensive. I also have a few more suppositions than DeRose puts forth. I imagine you’ll have your own by the end of this essay.

Since the 1920s, Memphis-based E.H. Crump, or “Boss Crump,” as he was locally known, dominated Tennessee politics. He had married into a wealthy family (the McLeans) and used that position to aggressively climb into power so effectively that eventually, he was able to place elected officials.

One of those officials, Paul Cantrell, is a main character in this story.

Cantrell, also from a moneyed family, starts his reign in 1936 when he is “elected” sheriff of McMinn County. He aspires to building his own political machine, and he starts by hiring Pat Mansfield as his chief deputy, a man seeking pay and prestige.

He continues hiring deputies, hardened men willing to bend rules, to make use of a Tennessee law that enriches both Sheriff Cantrell, Mansfield, and the rest of the deputies: all of them receive money for every person they book, incarcerate, and release. Each arresting officer gets $6 per arrest — equal to about $130 today — just by presenting a voucher signed by the sheriff to the courthouse.

Incentivized, those deputies comb the county, looking for minor infractions like “drunkenness” or “public lewdness.” When they find them, and even if they don’t, they assault the “perpetrators” and throw them in jail, often stealing their money in the process.

Even people just passing through Athens, the county seat of McMinn County, are victimized; deputies routinely board buses passing through and arrest passengers for drunkenness, whether they’re guilty or not.

Ayn Rand’s quote seems highly appropriate here:

“There's no way to rule innocent men. The only power any government has is the power to crack down on criminals. Well, when there aren't enough criminals, one makes them. One declares so many things to be a crime that it becomes impossible for men to live without breaking laws.”

Cantrell isn’t content with the considerable revenue he’s making from these illegal arrests, so he allows roadhouses to operate openly, collecting kickbacks from the owners of those establishments. Soon, practically the only people drawn to Athens are looking for prostitution, liquor, and gambling — the fruits of Cantrell’s illegal doings. It becomes common knowledge in Tennessee that Athens is “wide open.”

During his first four years, Cantrell presides over his extortion machine, using intimidation and brute force to extract money from the residents of the county. Employing former criminals to do his bidding, he amasses over a million dollars in today’s currency, and another million in the two years that follow. Cantrell is a small-town dictator, deeply disliked by his constituents.

But in 1941, there are larger issues on the minds of Athens’ residents. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, scores of young men from McMinn County are eagerly signing up and shipping out for training. In total, McMinn County supplies more than 3500 servicemen, out of only 30,000 residents, to the war effort. One family, the Sims, sends all four of their sons, plus their father.

As part of their training, these recruits learn the differences between democracy and fascist dictatorships. As one McMinn County soldier later recalled, “As they began to learn more about the totalitarian methods of Japan and Germany, many of these young men began to pay more attention to the undemocratic methods of the Cantrell machine.”

These men end up fighting all over the world, some in the most gruesome and vicious battles of World War II, including Guadalcanal, North Africa, Tarawa, and Omaha Beach. They become skilled, proficient soldiers, willing to risk their lives over and over for their beliefs.

A few names become main characters in this story: Bill White, Ralph Duggan, “Big” Jim Buttram, Knox Henry, Charles “Shy” Scott, and Ed Vestal.

While all those men and more are away fighting, the citizens of Athens become more and more enraged at being shaken down, abused, and in some cases, killed by renegade deputies. Disgusted with the abuse of power that is turning their formerly peaceful town into a corrupt, violent nightmare, they do what U.S. citizens are always told to do when we don’t like the circumstances of our city, state, or nation: in 1942, they attempt to vote Cantrell out of office.

His term as sheriff is up. Rather than seek re-election for that position, he decides he will run for state senator, and his chief deputy Mansfield will run for sheriff.

Let’s pause for a moment and talk about “poll taxes,” one of those terms that I memorized for the grade. In order to vote, you’d pay $1 to the county courthouse (valued at about $20 today), and receive a receipt that would allow you to vote at a future polling location. After the Fifteenth Amendment extended the right to vote for all races, Southern states and cities instituted poll taxes as a legal way to prevent black people from voting. It also kept poor people from voting, regardless of race.

Savvy politicians like Boss Crump and Sheriff Cantrell could, and did, capitalize on this system, paying the $1 poll tax for voters who couldn’t afford it, in exchange for their votes for machine-picked candidates.

On Election Day in McMinn County, the Cantrell machine swings into action like a huge malevolent octopus. Polling places are eliminated; armed deputies are stationed between voters and the ballot box; valid poll tax receipts are rejected, often by the official who had originally issued them; ballots are printed on virtually transparent paper so that officials can hold them up to the light and then write down whether the voter is a “friend or foe of the machine;” deputies publicly offer cash and whiskey in exchange for votes; phony absentee ballots are carted in… the list of election infractions goes on and on. I have to admire the machine’s creative cojones: groups of people even show up at the polls claiming to be blind, allowing the election officer to mark their ballots as he sees fit.

When official opposition poll watchers try to oversee the counting, deputies respond by saying helpful things like, “Sit down or I will shoot you down,” or “If you don’t like my count, take it to the supreme court.” They move the ballot box to the Cantrell Bank Building, and prevent anyone from observing the count.

No one is remotely surprised when “the results” are announced: it’s a total sweep. Cantrell and the machine win every single countywide office in a landslide. Cantrell is now a state senator, and Mansfield takes over as county sheriff.

Letters to the editor call the race, among other things, “a shame and outrage and disgrace to a free people anywhere on earth,” but the results stand, and Cantrell continues presiding over McMinn County through what is beginning to resemble martial law.

Soon, he owns it all: a lumber company, natural gas company, motor company and the local Cantrell Bank; the election officials meant to oversee the legality of the elections; the “elected” county office holders; and the entire police force, made up of thugs and murderers. Martial law is not, perhaps, an accurate description. Athens is run by a mafia, of which he is the indisputable don.

Desperate for outside help, citizens write to the Department of Justice. Three women even travel to Washington, D.C. to tell the U.S. Attorney General in person what life in McMinn County is like. They share with him their personal stories, including overheard conversations boasting that Cantrell plans to expand his machine to take over Boss Crump’s.

The attorney general is sympathetic, and a lawsuit is filed against election commissioners, but the suit goes nowhere when the two commissioners resign… and Sheriff Pat Mansfield and another Cantrell stooge slide in to replace them.

There’s a criminal case, too, from a prior election, and a federal jury convicts three Athens deputies for physically brutalizing voters, but the Cantrell-pocketed judge in the case sentences them to zero jail time and a fine of… wait for it… one cent.

In September of 1944, deputies shoot and kill a Navy sailor in Athens, home on leave, claiming that he was disorderly, drunk, and charged the deputies with a knife. Is it any surprise that the deputies get off scott-free?

As the war rages on, a mother of six Athens men fighting overseas writes, “It is hard to see our boys making the sacrifice they are making for a freedom that we don’t have in our own country.” She speaks for many.

Germany surrenders in 1945, and Bill White comes home after three years fighting abroad to attend the funeral of his grandfather. By now, White is a fierce soldier, having survived the bloodbath of Guadalcanal by killing countless Japanese in close combat. He is jumpy, hair-trigger, restless. He is not to be trifled with.

While he’s home, his father tells him what’s been happening in his absence — events left out of letters so as not to burden him — including his father being jumped by deputies and dragged to jail for carrying a milk bottle (they claimed it was alcohol), then fined ($320 today).

In White’s words later, “everything, everything, everything you’ve been told you’re supposed to be fighting for wasn’t there.”

Other veterans, arriving home to civilian life, agree. By the start of 1946, all of the servicemen have returned. The local newspaper, the Post-Athenian, writes: “1946 begins as every year does, with a question mark. And it is well to remember that you and I and the rest of the common people — by God’s grace — alone hold the answer.”

Elsewhere, the mood across the U.S. is jubilant, optimistic. Colleges are filling with returning men; the economy is booming, as is the birth rate. The GIs coming home to Athens, however, find a hometown that is almost unrecognizable, like George Bailey in It’s A Wonderful Life encountering “Pottersville” instead of Bedford Falls.

Local businesses in the town donate funds to create a VFW in the basement of the Robert E. Lee hotel, and there, the GIs spend time recounting stories from the war and attempting to find their footing. The also commiserate about the state of Athens, calling it: “a jail,” “like Nazi Germany,” run by “storm-troopers, drunk most of the time, beating up our citizens for the slightest reason.”

They decide to formally challenge the machine. They meet regularly in secret, hiding their plans from their wives and parents, speaking in code on the phone, and mobilizing support for their cause, quietly and carefully, within the community.

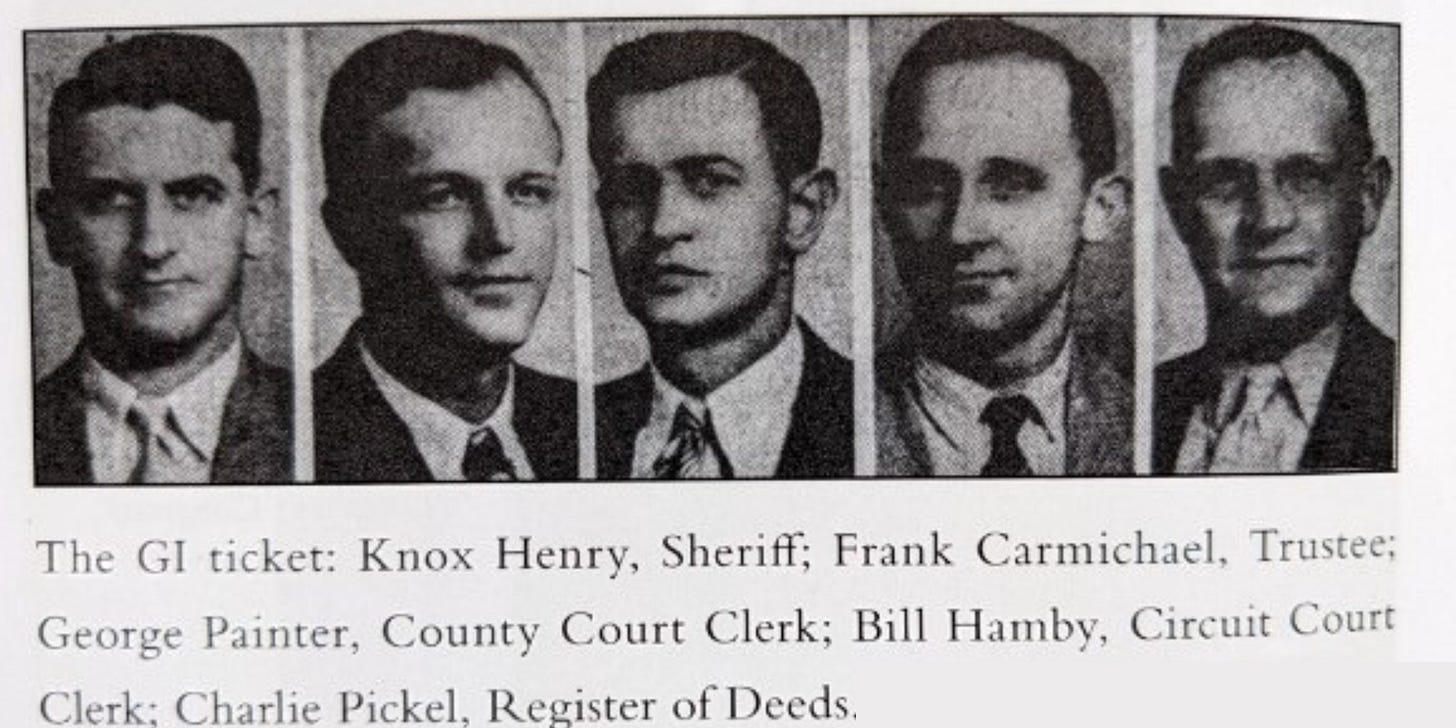

In May, after much behind-the-scenes work, they announce their plans by placing an ad in the Post-Athenian, inviting all ex-servicemen and women to a meeting, where they will nominate five veterans as candidates for office on the newly-created “GI ticket.”

The ad draws over 300 veterans who enthusiastically approve all five nominations, with Sergeant Knox Henry for sheriff leading the ticket. The meeting also installs a “GI executive committee” to lead the campaign, made up of the five candidates plus 23 other GIs. “Big” Jim Buttram is hired to lead the campaign.

With about $8,000 in the coffers — donated mainly by fed-up local businessmen — and an endorsement from the Republican Party, the candidates start campaigning in earnest. They form “combat teams” and comb the Blue Ridge Mountain foothills all day every day, door-to-door and farm-to-farm, meeting face-to-face with just about every voter in McMinn County.

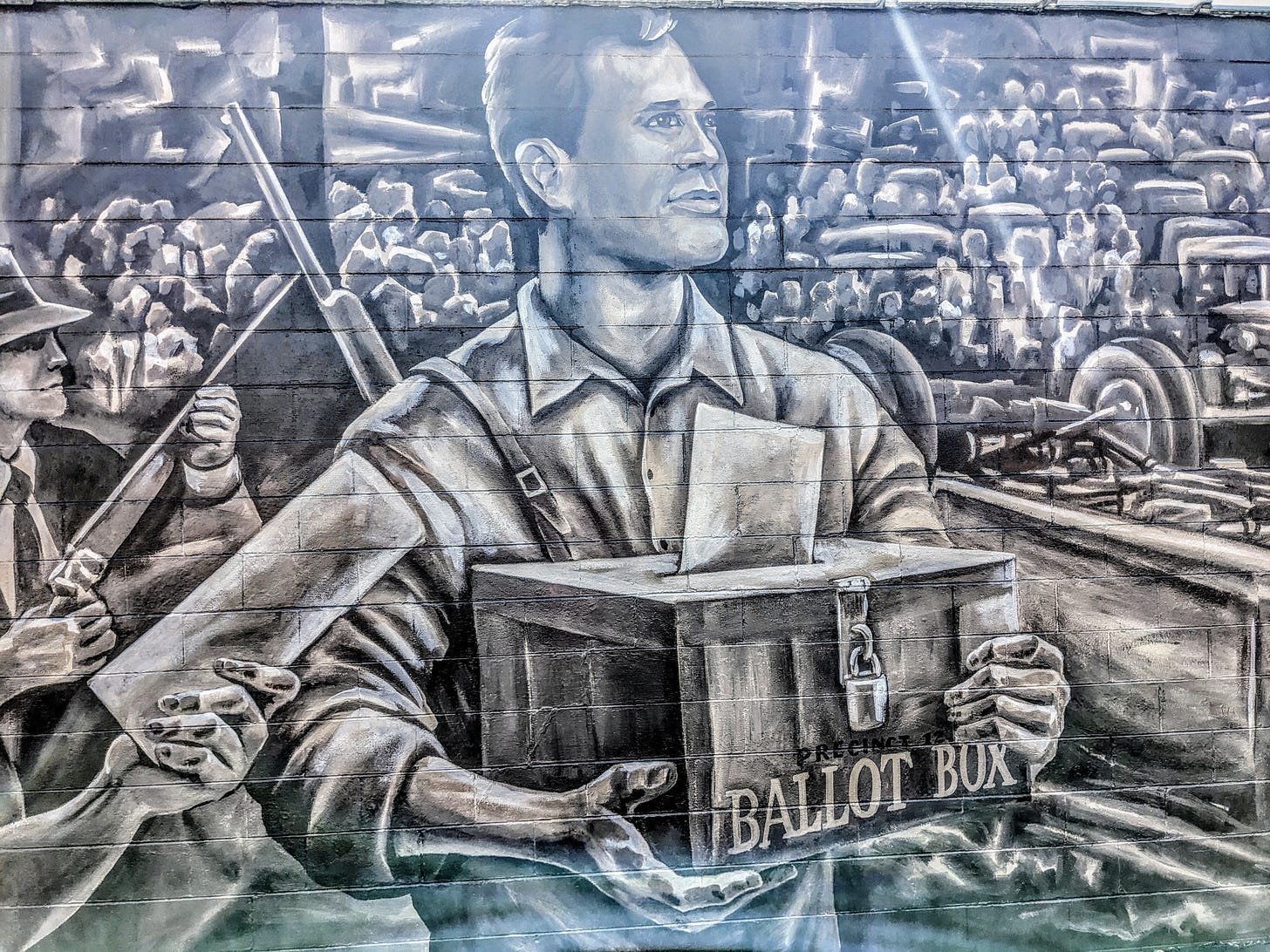

All summer long they blanket the town with signs, drop leaflets from planes, and shout through loudspeakers driving through town. It’s an organized, committed, all-out assault, and it seems to be working. McMinn residents resonate with the oft-repeated GI promise, “Vote GI. Your vote will be counted as cast.”

Predictably, the Cantrell machine is not sitting idly by. Rather than campaign, however, the deputies unleash their malice upon the opposition, tearing down signs, roughing up poster-hangers, and doing what they do best: intimidation.

Anonymous phone calls threaten GIs in the middle of the night; post cards arrive in the mail, scrawled with menacing messages. A deputy even clubs Knox Henry’s friend “in the street, right next to him.”

As George Orwell would say, not that many years later,

“All tyrannies rule through fraud and force, but once the fraud is exposed they must rely exclusively on force.”

Almost as if channelling Orwell, Bill White challenges the assumptions of the GIs running against the machine:

“Do you think they’re going to let you win this election? Those people have been taking these elections for years with a bunch of armed thugs. If you never got the guts enough to stand up and fight fire with fire you ain’t gonna win.”

White turns out to be exactly right.

I love history - at least, that's the story I like to tell myself. In reality, I also spent a great deal of my time ignoring the lessons of history...choosing instead to do whatever I could to get that grade...and I felt my instructors were on the same page - they were doing whatever was necessary to get paid. Teaching and learning failed...and I never learned about the Battle of Athens (until now). But then again, after reading this first part, I'm not surprised this (too) was swept under the rug as I kept hearing how great America is...how it's the best in the world. I had my doubts...I still have my doubts.

Yay!! You're back! OK then, you've got me hooked. See you next week. xox