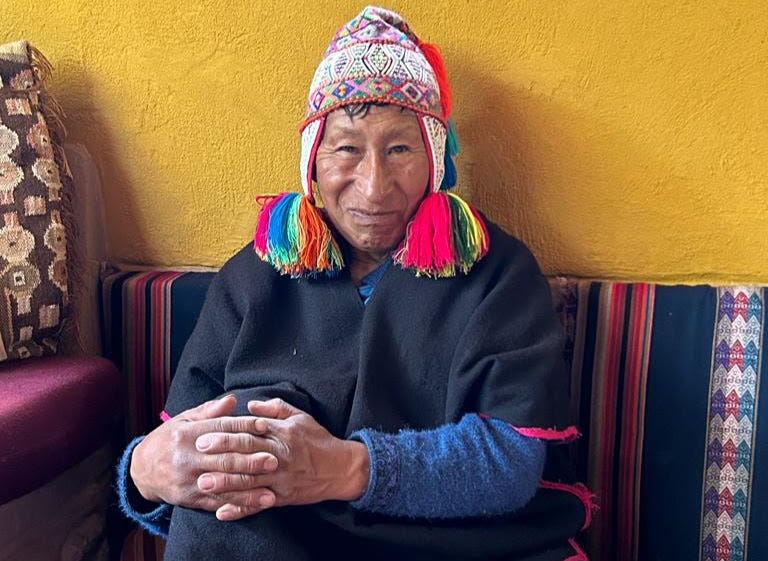

I’m in Peru, sitting across from Benito, the diminutive Quechua shaman who holds dried coca leaves in his fist. He repeats my first name over and over while blowing on the leaves, petitioning Pachamama, (pacha = earth, mama = mother) for her guidance on my behalf. What does the divine Mother Earth want me to know?

He throws down the leaves a few at a time, making a random (to me) pattern, and he stares at them, nodding. He speaks in Quechua. His interpreter listens, then looks at me earnestly and translates:

“Enjoy your time here in the Sacred Valley. You have much to learn. And it is very important to do it one step at a time. You are a like a child, still much to know to become a spiritual leader. There is no hurry. You will learn a great deal while you are here, which is good because you will need it when you return. You will need this knowledge, this new perspective.”

I take in these words, then, as usual, default to thinking that thinking will be the key to enlightenment. By virtue of excess pondering, I’ll hit on some revelation, and that will change me into the person I want to become.

Oh, silly, silly girl.

I did have much to learn, and damn, did I learn at least one small part of it.

Adversity is a monstrously huge topic, so I’m going to take it, as Benito suggested, one step at a time. I’m not going to hurry. I’m not going to try to cram everything I feel and think and want to share into one essay.

Progress.

I’m fairly certain that the last three years have created tremendous upheaval in your life. My guess is that, at some point, you’ve experienced the following:

great confusion, disillusionment, or anger;

a changed job or living situation;

disagreements with family and friends, perhaps so much so that relationships have suffered, even severed; and

the loss of dear ones who’ve died.

Yes, all of those are part of the human experience, but never in my lifetime (I was born in the mid-sixties) have all those adversities occurred in such a compressed period. It’s clear to me that we’ve moved into a new phase of our evolution as a species, one that I like to think of as a pressure cooker.

I know, I know, we use that term all the time to describe something that’s intensely difficult — “working as a stock analyst was a pressure cooker!” — but we rarely recognize the beauty of what a pressure cooker actually does.

It’s a device that accelerates the process of transformation. What would take hours is accomplished in minutes. Dry granules morph into moist fluffiness.

What is hard becomes soft.

What is cold becomes warm.

What is dense becomes light.

Quickly.

With that in mind, let me introduce… the sweat lodge.

Growing up, I’d never been averse to heat. As an adult, I used an infrared sauna we bought for my husband for health-related issues, enjoying it liberally until I was told I had rosacea and that excess heat was a trigger. After that I avoided saunas, hot tubs, and red wine. (I ignored the advice about chocolate.)

Later, after I cured myself of the rosacea — a story for another day, one that did not include allopathic medicine (surprise!) — I still had a knee-jerk reaction to overheating. So when the opportunity to partake in a traditional sweat lodge ceremony arose, I had some trepidation about it, particularly the length of time we would spend in the lodge.

I asked a cluster of my fellow trip-goers who had done the lodge already to tell me what the experience is like, and they gave me an overview: we would be in a circle together in the “lodge,” which was really a handmade tent of wood supports and wool blankets, for four “sessions.” Each session is about 20 minutes, and after each one, a flap to the tent is opened to cool it down. These breaks can last anywhere from five to 25 minutes.

Okay, I thought, I can deal. As long as I stay hydrated, I should be fine!

I must have said that last part aloud because I heard someone say, “Water isn’t allowed until after the third session.”

“What?!?” I said, very aloudly.

They were quick to reassure me. “You can do this,” they said. “It’s so worth it. And if absolutely necessary, you can leave at any time.”

I trust these women, so I show up at the appointed time and place, nervous but game.

Next to the dome-shaped tent, a fire smolders. Large stones nestle at the heart of it. Ripples of heat carry flecks of ash hither and yon.

Ten of us receive a cleansing smoke-blessing from our intrepid shaman Arturo, slug down a few last gulps of water, then drop to our hands and knees one by one to crawl into the lodge.

It is small, far smaller than I anticipated. I sit cross-legged, and notice that if I straighten my spine completely, my hair grazes the side-blanket as it curves above my head. I will have to crouch.

As we all pack ourselves into the tight circle around a central pit, Arturo welcomes each of us with a hearty “Aho mateo!” the full meaning of which I’m still not clear. I know “Aho” is a Native American affirmation of unity and connection with the spiritual world, but “mateo” was never defined for us. Regardless, “Aho mateo” becomes our call and response for the rest of the ceremony.

Arturo welcomes us and prays in Spanish, much of which I understand. He’s clearly not just a shaman, he’s a poet. Maybe those necessarily go hand-in-hand.

In English, he explains what I learned from my friends, and when the ten of us nod our understanding, the ceremony begins in earnest. He calls out to Julio, his assistant outside the tent, who begins sliding in the baked stones one by one.

Arturo picks each one up with a set of antlers as though using a pair of salad hands, and deposits it into the pit, singing a chant in Spanish that welcomes the stone as an “abuela,” an ancestor. Enough stones make their way into the pit that soon we all know the words and join in the singing.

He smudges each rock with what smells like sage, shouting “Aho mateo!” and we respond in kind, “Aho mateo!” The sage incinerates on contact, transforming into a squiggle of smoke that disperses into fragrant haze above our heads.

More stones arrive, and their collective heat emanates from the center of the tent. Eventually, Julio delivers a bucket of water, and closes the flap. Darkness envelops me. Here we go, I think.

Praying aloud, Arturo scoops water onto the stones which hisses into steam, filling my nostrils. The heat is intense, but bearable. He plays the drum, the beats loud and rhythmic, and he chants syllables I do not understand.

I shift positions, trying to get comfortable. But we’ve left comfort far behind. The heat grows, and grows, and grows some more. It’s becoming oppressive. The sweat starts, then just pours off me, more than I’ve ever experienced in my entire life.

The mounting heat, plus the almost-total darkness, plus my necessary crouching creates a low-grade panic. Sitting up becomes more and more difficult as the heat rises higher. I start to feel trapped.

I wrap my arms around my knees and keep my head down. I close my eyes. I’m okay, I think. I’m not going to die in here. But I’m not actually convinced. Fear is creeping in. I’m getting overwhelmed. What originally felt bearable is feeling increasing less so.

I keep trying to take myself in hand. But I am flashing back to other times in my life when I was overwhelmed with panicked helplessness, when I was stuck in I can’t; it’s beyond me; it’s too much; I give up.

I start sobbing. I am sliding down the wall of my childhood home in Ohio, having just heard that my mom tried to take her own life.

I am back in the driveway of our house in Connecticut, running out of time to get the last belongings into the truck. No wait — I am in New York, doing the same damn thing. (What is it about moving and me??)

I am on the way to the hospital, in labor with my first child, gripping the dashboard in a pain I have never imagined before.

This sweat lodge is pushing me to the brink, and I’m collapsing. Tears and sweat, sweat and tears… they are all one. I am in serious distress, and I want out. I curl up into a fetal position, my face pressed into the earth, my running nose dripping into the dirt. I am as low as I have ever been.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, I feel a hand on my back. In that darkness, I am not alone. It’s Cynthia, sitting to my left. Her fingers smooth my spine, gently, over and over: not alone, not alone, not alone.

A tiny molecule of hope enters my consciousness. Arturo keeps drumming and singing and the heat keeps mounting, like a relentless nightmare. But is my fear shifting?

My mind drifts back to three days earlier, when I climbed a short mountain that overlooks Machu Picchu. The climb up scared the shit out of me, but at the top I realized: it was a psychological test masquerading as a physical one. I was in no actual danger. It just looked like I was.

The climb down was totally different. I saw the path for what it was. I focused on each foothold, not on how close I was to potential death. I remembered Benito’s simple, wise advice, and took it one step at a time. I breathed.

Here in the lodge, with my friend’s hand on my back, I commit to clearing my mind of fear — not by thinking “I’m not afraid, I’m not afraid” but by breathing in the truth of my strength, over and over: I am strong.

I can feel my heart expand a tiny bit. Yes. This is the truth. This is true for us all.

The first session comes to a blessed end. Arturo shouts “Aho mateo,” which we echo, and Julio opens the flap from the outside. Light spills in. Cooler air follows.

I raise myself onto my elbow, my head still hanging down. I squint at the light now illuminating the dirt in front of me. My eyes feel sticky; I wonder what all this heat is doing to my contact lenses.

I’m in limbo. I don’t feel helpless anymore, but I also don’t feel strong. I’m just an empty vessel, clinging to that hope molecule.

Arturo starts to speak in English, then stops, saying, “It is hard to say this in English.” I hear myself respond immediately, “En español.” I don’t know why or how; a moment earlier I thought I was empty. I thought I had nothing to give.

So he prays in Spanish, and I translate. I somehow conjure up enough strength to channel the meaning from Arturo to the rest of the circle, even though I’ve never thought my Spanish was particularly wonderful.

When he says, “Sometimes a hand comes to you, and it is the hand you have awaited all your life,” I feel something inside slide into place.

Yes. How perfect.

From that point on, even as the flap closes again and the heat returns, I am calm. More emotion arises, and there is more learning, forgiveness, and growth, but the fear and panic are gone.

During the rest of the three sessions, as more stones arrive and the ferocity of the heat cracks them in half, I wave goodbye to my ego and send it packing.

I lie in fetal position the whole time, happy to mash my cheek to the dirt. It is the closest I have ever felt to being one with the Earth. The ground accepts my tears and the rivulets of sweat that cascade off my shoulder blades. Pachamama’s willingness to take it all comforts me.

It is also a tiny bit cooler down here, and that works better for me. I think, I don’t need to prove anything by sitting up and muscling it through the hottest part of the lodge; I just need to survive in whatever way works for me. There are no prizes here, no awards handed out at the end. Enduring the heat is the only game; endurance is the prize I will carry with me out of this lodge.

And then another truth reveals itself to me: If I can survive bringing three children into this world without drugs, I certainly can survive this.

I state this revelation in a sharing circle that Arturo leads later in the ceremony, during one of the breaks. Many hours after the ceremony, one of my fellow sweat lodgers —and a fellow mother — will tell me that the truth of that statement for herself gave her hope and helped her endure the ordeal.

The birthing motif continues to bring insight. I am experiencing a rebirth of sorts, a do-over from the emergency caesarian section my mother had when I was born. I have always suspected that my detour around the painful birth canal squeeze doomed me to a lifetime of procrastination and a lack of discipline.

But in this darkened womb of pulsating heat and burning sage and cracked rocks, I’m getting another chance. I’m pushing through the discomfort and fear this time. I’m meeting the challenge. Will that change the trajectory of my work habits? I believe it will.

Arturo sings and drums and prays all throughout. We “Aho mateo” more and more forcefully until the very end, when Julio opens the flap for the last time. I crawl out, stopping first to place my forehead to the ground and thank Pachamama for her gifts, and for the transformation I have just experienced.

Two hours after crawling into that blanketed pressure cooker, I crawl out, reborn.

What was hard has become soft.

What was cold has become warm.

What was dense has become light.

Thinking did not create the transformation; enduring discomfort did. Surrendering tears to the Earth; hands reaching out to touch; words of strength: by these we endure.

Nine days later, something Arturo said still resonates inside me: “The heat of the fire is the medicine. And we human beings are medicine to the Earth as well.”

I hope you’ll join me next Sunday for Part II of Welcoming Adversity.

Wow, what a journey! I filled my soul with your words today, not only because it’s been a while and I’ve missed you, not only because I intentionally wanted to start the morning with your wisdom as soon as I saw that you had put out a stack, but also because as soon as I saw the title, I knew the universe was about to offer the insights I most needed right now through its adventurous child that goes by Mary. You brave and curious wonder. Yes, the epiphanies don’t come from thinking but through the suffering! A reminder that needs daily repeating. Looking forward to part 2. And I’d love to see some more photos!

This is beautiful, powerful well-cooked wisdom. Thank you, Mary!! I feel the medicine