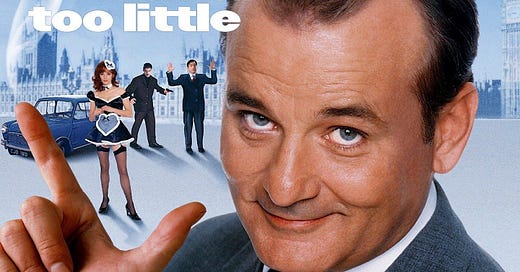

I watched The Man Who Knew Too Little recently. To be clear, it’s not a perfect movie by any stretch; the ending is disappointingly lame and the pace drags, but the bulk of it bubbles along with good-natured humor.

Here’s the set-up: Bill Murray plays Wallace Ritchie, a hapless American who drops in to visit his successful younger brother James (Peter Gallagher) in London. Too busy with an important dinner party to celebrate Wallace’s birthday that day, James buys Wallace a ticket to participate in an elaborate role-playing improvisational theater performance.

However, Wallace accidentally receives a call intended for an actual hit man and gets caught in a web of intrigue, completely unaware that the action unfolding around him is real.

I won’t give too much of the thin plot away since that’s not the point of this essay, but you can probably imagine much of the humor inherent to the situation. Wallace interprets everything that happens — phone calls, car chases, attempts on his life — as “part of the show.” He even assumes that the romantic interest shown by his “co-star” must be contrived.

I’m sure my former acting career and deep love of teaching improvisation as a spiritual practice may have predisposed me to enjoy this slight film, but there’s something else at work here, and it has to do with fear.

I’ll never forget watching my youngest son Henry at four years old fling himself down a monster sledding hill with total abandon, hitting a massive snow jump built in the middle, and catching at least 3 feet of air.

The teens on the side of the hill paused as they dragged their saucers, marveling at the tiny courageous speed demon flying through the air: “Duuude, check out that little kid! Shit, that’s awesome!!”

What the teens didn’t know is that I had mistakenly lined my little Henry up with the jump in such a way that he had no way to avoid it. He bombed the hill, trusting me and thinking of course he’d be safe; why would he believe otherwise?

And he was. He held on to his sled, sailed a good eight feet, and stuck the landing safely at the bottom of the hill. People clapped.

I slid-ran down the snowy slope to check on him, and found him gathering the rope to head back up the hill, eyes sparkling. “That was GREAT, Mom! I want to do that AGAIN!”

Henry and Wallace Ritchie’s common denominator? Trust masquerading as bravery. Both of them looked superhumanly courageous, but both of them just believed that the danger facing them wasn’t real. Both of them were tricked into courage.

One evening years ago, during my YogaDance teacher training, I was gratefully soaking in the whirlpool when I became dimly aware of a woman entering the room and standing at the edge of the ice-cold dunking pool. I had briefly considered a quick dip in it, before I had dismissed it entirely as a chilly bridge too far and settled into the welcoming heat.

But there she was, swinging her arms and bouncing lightly on her toes, preparing herself for the plunge. She flicked her wrists as though shaking off unwanted insects, and exhaled “Hoo!” and “Ha!” forcefully, all in high spirits and effervescence.

Would she really do it? Suddenly, she went. Down the three steps she plunged, shaking and shimmying, singing and hooting, laughing and sighing. I couldn’t stop myself — I laughed out loud at the wild freedom she allowed herself. She was a trip!

She must have heard me, because when she emerged, she sought out my face. “Hoo!” she exclaimed, grinning at me. “I’m so afraid of the cold!”

Then to my great admiration, she repeated the same uninhibited rituals and went back in, two more times. Alternately laughing and shrieking, she showed me a new way to handle fear. This was no exercise in serious stiff-upper-lipped-ness; this was a master class in wild, wooly, let-it-all-go-saying-yes-ness. She inspired me.

Breathing hard, she rose from the pool for the last time and waved goodbye. Without much thought, I rose from the heat, light-headed but determined. I was half-way down the tile steps before the shock of cold registered, but by then I was committed. I let out a joyful, uncharacteristic whoop, which somehow allowed me to sink all the way down, reveling in the exhilaration of contrast and a new version of bravery.

My daughter Maddie, who has overcome tremendous odds and very real fear (an essay/book in itself) recently said, “Have you ever noticed that once you push through a fear, once you’re on the other side of it, you realize it wasn’t all that dramatic or impossible? You realize that it was your anticipation of it that was far worse than the reality of it?”

She said that because I’m struggling these days with the sale of our house. I know it’s the right thing to do, and the right time to do it, but I feel fear about it. I’m afraid of walking away from this place where we’ve raised our three children, planted fruit trees, welcomed family gatherings, and walked among blinking fireflies in the magical dark meadow. It feels like home.

How can I leave all that?

Well, there are very practical reasons: my children are grown, the place is large, and it requires a lot to keep it going. There’s also the issue of living in a state (New York) with the highest taxes and the least amount of personal freedom, as calculated here and here and here.

The difficulty in selling it is based on the fear that I will never live anywhere else that compares to what I have. Yet that’s kind of crazy, isn’t it? There must be other beautiful places in the world, places I can’t even imagine right now. Places that I can’t see, won’t see, unless I’m free to find them.

Heck, I left behind the house we lived in before this one — a beautiful place, too, that felt like home — and that departure lead me to the one we’re in.

I’m not alone in my fear of letting go of Door #1 in favor of Unknown Other Doors. Studies show that fear decreases risk-taking; “intolerance of uncertainty” is a thing. When human beings are faced with making a choice, we conjure up horrible outcomes more often than wonderful ones.

So how does all of this relate to Wallace Ritchie and my son Henry?

Wallace and Henry had no fear, because they believed they were safe. It was a mistaken belief, but one that worked in their favor — because in a marvelously ironic twist, their lack of fear actually may have ENSURED their safety.

Wallace was totally relaxed in every scenario, so relaxed that he could respond with perfect, instinctive reflexes to every life-threatening event. Henry flew down the hill and over the jump successfully, because his body, in a state of assured confidence, did what it needed to do without hesitation or second-guessing.

Neither one of them was afraid of making a mistake, because in their beliefs about their situations, there were no mistakes to be made. Henry had complete faith in his mother and was not old enough to imagine gruesome outcomes.

Similarly, Wallace had total faith in the situation around him. He “knew” that it was all “make-believe” (an interesting word, no?) and that there was no right or wrong way to do it.

I can attest to the feeling of fearlessness that comes with participating in theatre improvisation. Because there’s no script, no plan, no expectation of outcome, and no mistakes to be made, it engenders bravery. The old “What would you attempt if you knew you could not fail?” refrigerator magnet is altogether appropriate here.

Both fear and fearlessness rest on belief. But why do we believe what we do? Mainly because we’ve been told that the world is a certain way, or we are a certain way. Sometimes our beliefs turn out to be true; sometimes they don’t. My mother told me “Poindexters aren’t creative,” and I held on to that belief for far too long.

When you get right down to it, everything is hearsay except for the experiences we experience ourselves — and even those experiences are filtered through our five puny, fallable senses.

Frankly, the whole structure feels terribly tenuous. Here we are, making life decisions based on fear, which is fueled by these inordinately powerful, yet flimsy, unverifiable, and highly malleable beliefs.

There must be a better way.

What if everything you’re afraid of isn’t real? Or better yet… what if you choose to believe a different reality, one that includes your ultimate safety no matter what you do? Might that belief actually create the safety you so desperately seek?

What if Wallace and Henry were not mistaken in their belief that all would be well?

Look, what I’m suggesting is a major leap, I know. I’m asking you to sink into a place of faith that this world we see and touch and feel is not all there is. It’s not an easy jump, especially because most of us are taught the opposite: if it’s not measurable, it’s not real.

We are taught that the reality our limited five senses dish up to us daily is the only reality. If you choose to believe that, then this rollercoaster ride of being human is all about trying to have the smoothest ride possible. Avoid pain at all costs. Take no risks.

But if you believe that this material world is only one reality, and like Wallace and Henry, you are always and already safe, then your entire life can be an improvisational exercise with no right or wrong way to play the scene. Fear diminishes. Levity returns. It’s all a game.

Which brings me, finally, to the woman in the dunking pool, who let her fear be part of the game, rather than letting it stop the game.

Yes, I trust that my true home is not of this world, but there are still steps in this world that must be taken. I have to get the house ready, put it on the market, box up my belongings, and say goodbye. All real tasks, some that require real courage.

That exuberant, joyful woman taught me that courage does not have to be grim. Far from it. Her wild, fear-conquering rituals showed me: I can meet my fears laughing. I can dance through them. I can play the game.

Wonderful! Thank you, my friend.

Again - you articulate things so well - I could see Henry flying down that hill; I could feel the descriptions you wrote. And I have a few of those stories (which I have to keep reminding myself of when I get too ensconced in how I think things are). And I may have to go find that movie...