What My Effed-Up Spine Taught Me About Trauma

Sometimes, our bodies hold stories that keep us trapped in pain

Sometimes, our bodies hold stories that keep us trapped in pain

My neck hurts.

“Do you want to see what the problem is?” asks Dr. Rob. He’s staring at an X-ray he just took of my neck.

“Of course,” I answer. I can’t wait to see physical proof of whatever is holding my neck rigidly in place. After months of physical therapy and on-and-off years of looking like a newbie boot camp recruit, I’m more than ready to see what the hell is going on in there.

I stand next to him in front of the large computer monitor, our faces lit with ghostly blue light. It takes a moment for me to fully understand: Oh, that’s my skull, my vertebrae. Those are my teeth, not a picture of some dead person’s insides. Somehow this doesn’t seem possible. How can I be fully alive and look like a skeleton at the same time?

I must look confused because Dr. Rob asks, “Have you ever seen your spine before?”

“Yes,” I lie, without realizing that I’m lying. It’s something I do sometimes, to be agreeable. It takes me a few seconds to reach back into a half-century of memories and come up empty.

“Okay,” he continues, “then you’ve seen your kyphotic curve?” Now I’m stuck. A previous chiropractor ordered X-rays years ago but I never saw the actual slides. All I heard then was “effed-up neck” (not what she said, but what I heard), so now I don’t know what else to say. I nod in a general sort of way, hoping this new chiropractor will explain more. He does.

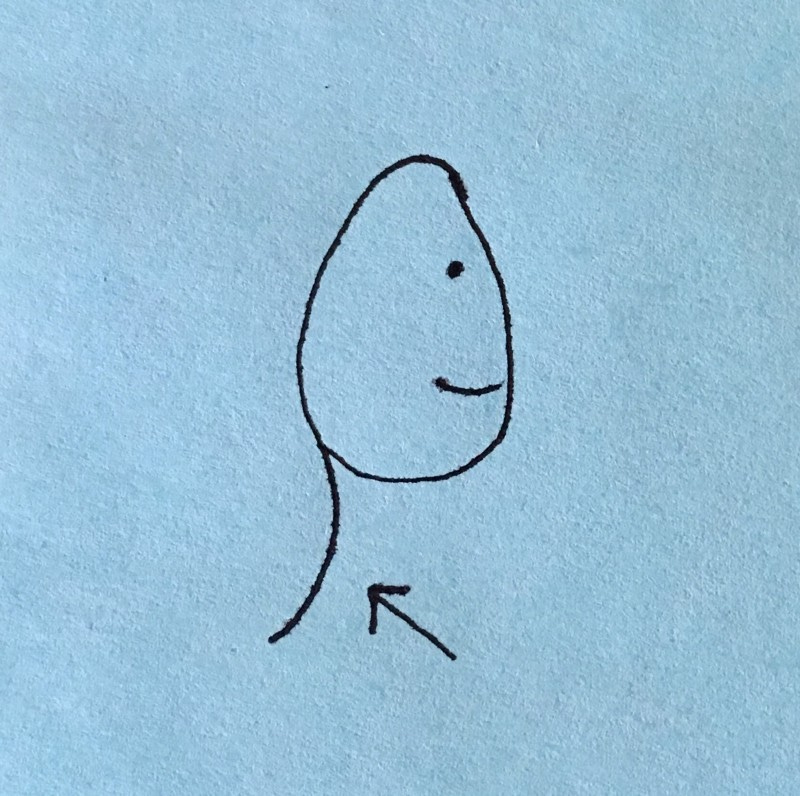

Basically, the cervical spine should look like this:

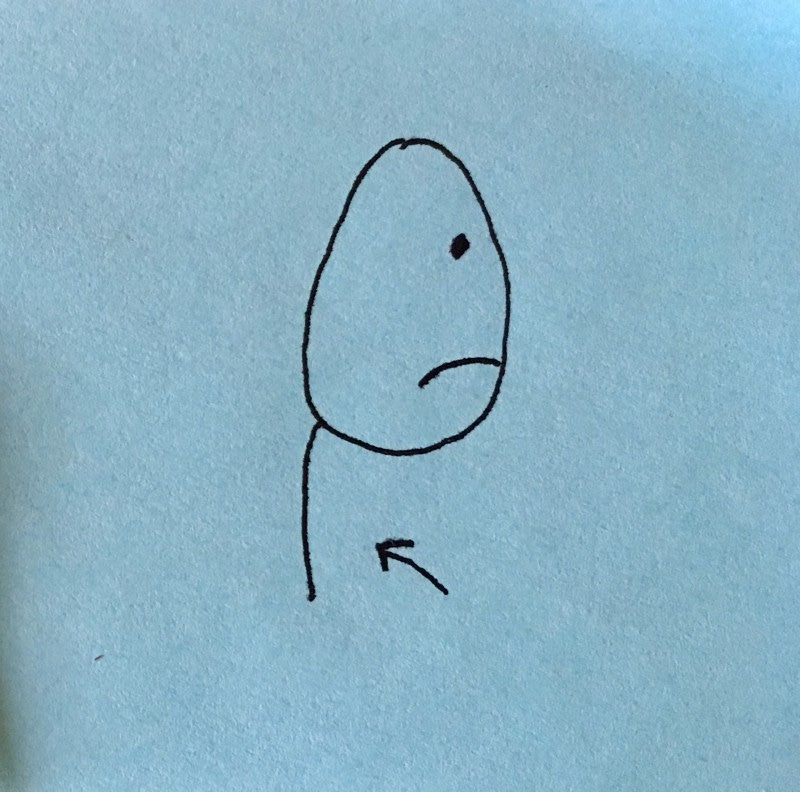

In me, it looks like this:

That’s why I can’t check my blind spot over my left shoulder when I drive or look up at the sky during triangle pose in yoga. That’s why I get headaches and hear crunchy noises when I nod yes or attempt to look both ways before crossing a street.

“Holy shit,” I exclaim, then “sorry” in case I’ve offended him. I don’t really know Dr. Rob.

He laughs. “No problem. Yeah, holy shit.” I like him.

He continues: “Were you ever in a car accident? Whiplash? Some other kind of neck trauma?”

I start to try to shake my head no, which I usually do with my entire upper body, but then I stop. The words “neck trauma” hang in the air as I see myself at ages seven, eight, nine, and 10, hanging from my older sister’s hands which are cupped under my chin and occiput.

I’m a party trick for her amusement and, on occasion, entertainment for her friends. She lifts me off the ground by my head, a demonstration of both her strength and my unquestioning obedience.

I’m a willing participant, certainly, since hero-worship generally implies as much. I would have eviscerated myself with a steak knife had she requested it or even merely suggested it. Allowing myself to dangle like a kitten hanging from her mother’s teeth was the least I could do to remain in her good graces. What harm could come of it?

I show up twice a week at his office, he adjusts my neck, and I burst into tears.

I describe the party trick, ending with a feeble, “So, I don’t know if that’s what you mean by neck trauma?”

He guffaws. “Um, yeah. That qualifies.”

Over the next few weeks, we begin the long process of reversing my reverse curve before it becomes irreversible. I show up twice a week at his office, he adjusts my neck, and I burst into tears. We both get used to it.

The first time it happened, he asked, “The C5 and C6 vertebrae are connected energetically to the throat chakra. Is there something you’re holding onto? Something you’re not saying?”

In between my herky-jerky breathing, I issued a microscopic “yes,” and then fell silent.

My YogaDance training taught me that the seven chakras (spiritual energy centers located along the spine, neck, and crown of the head) are vital to overall health. Each one corresponds with physical organs as well as emotional and spiritual well-being; specifically, the throat chakra governs communication and “speaking one’s truth.”

So each time he adjusts me and I cry, I consider my possible answers to his question:

I’m a co-dependent person who hates labels and thrives on outside approval, being liked, and keeping the peace.

I’ve been willing to trade integrity for harmony.

I’m beyond terrified of telling the world what I really think, including telling my sister to put me down.

Each time, I decide not to dump all of that on Dr. Rob’s doorstep. Instead, I keep getting adjusted, silently submitting to the pain and allowing the tears to flow as recompense.

I wanted to be just like her. She was nine years older than I was and I thought she was perfect. I brushed her long blond hair. I took dance lessons with her. She played tennis, so I played tennis. She acted in high school, so I did, too. She was a writer and a damn good one.

I adopted her walk and her facial expressions as my own, so much so that when she introduced me to her future husband, he said to her, “Hey, you’re just like your little sister!”

“She is like me,” she hissed, evidence of the schism that had already appeared in our relationship.

I never knew why she shut me out, why it all of a sudden felt like she hated me. I still don’t know for sure but my younger self decided that it had something to do with the competition. To win her back, I had to stop winning. I had to keep a lid on myself, my accomplishments, and my writing.

One day, as I leave Dr. Rob’s office and walk back to my car, I stop in the parking lot. On the ground directly in front of me is something blue. A brilliant blue, out of place on the gravel. A feather.

It makes me inordinately happy and I can’t explain why. I take it home with me and place it on my writing desk, where it stares at me with reproach while I find all manner of ways to avoid writing, including looking for part-time jobs and deleting junk mail from 2013.

Eventually, in my heroic quest to avoid the one thing that I’ve said I want to do with my life, I Google the meaning and significance of a blue feather.

Well, knock me over with a…

“Self-expression,” the first result says. “Freeing the throat chakra.”

I stare at the feather like a joyful idiot, in awe of its perfection.

For decades now, my sister and I have bridged our physical distance through newsy emails. I tell her about my kids; in her ridiculously well-written missives, she tells me about hers. Our relationship feels stable and calm.

When we were walking on a beach together a few years ago, I asked if she still wrote. She said she did — mostly poems, short stories, and such.

“Do you send them out?”

Her response was a short bark of a laugh, followed by, “God no. Of course not.”

I remember this comment as I continue to stare at the feather. I cannot ignore it or its message, and I don’t want to anymore. My neck won’t let me. I sit down to write this essay, to open up the quiver of my heart.

I place an arrow of truth, adorned with blue feather fletching, on the string of my beautiful recurve bow… and let it fly.