I’m standing at a cocktail party in 2004, doing what you’re supposed to do at gatherings like this when you don’t know a soul: converse lightly with strangers about inoffensive topics.

My husband Peter and I are relatively new to Brookfield, Connecticut, having moved here just a few years ago, and we somehow got invited to this neighborhood get-together. There’s finger-food and laughter, hugs among friends, ice in heavy-bottomed glasses. I feel welcome and apart, both, like I’m at an audition of some sort, so I smile a lot and ask many questions. I know the drill.

We find ourselves repeating the same story, variations that shuffle the order of the following: moved from Westchester County, NY for a Waldorf school in Newtown, CT; three little kids; stay-at-home mom; Pete commutes to Mount Kisco to run a security-guard company; the house is on Long Meadow Hill Rd.

We drift from couple to couple, making the rounds, trying to remember names. Then, out of the blue, a question: “where on Long Meadow?”

I give a more exact description of where we live, and one half of the pair in front of us nods, saying, “Oh… okay. That’s the house with the kids always playing outside.”

It’s been almost 20 years since that comment, and it still stops me cold.

In January of this year, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy stated that he believed age 13 is too young for children to be on social media platforms. This week, he upped his message, putting out an advisory that claims excessive social media use “can be a profound risk” to teen mental health.

“Can be”? Really. How bold.

Phrases like “ample indicators,” “raise serious concerns,” “further investigation,” and “urgent consideration” litter this tepid report, which toggles between faux-imperatives like

“Now is the time to act swiftly and decisively to protect children and adolescents from risk of harm,”

and craven cop-outs like

“At this time, we do not yet have enough evidence to determine if social media is sufficiently safe for children and adolescents.”

I see. So the statistics that are stated in the report like:

up to 95% of youth ages 13–17 report using a social media platform; more than a third say they use social media “almost constantly;”

one-third of girls aged 11–15 say they feel “addicted” to social media;

adolescents who spend more than 3 hours per day on social media double the risk of depression and anxiety;

8th and 10th graders spend an average of 3.5 hours per day on social media; and

greater social media use among 14-year-olds predicts poor sleep, online harassment, poor body image, low self-esteem, and higher depressive symptom scores

are not enough effing evidence??

Sorry. This stuff fries me. Here’s what they should be saying, if they were remotely honest:

“Since ‘robust independent safety analyses on the impact of social media on youth have not yet been conducted,’ we will keep our fat asses nailed to the fence until some exhaustive, 20-year, random-sampled, peer-reviewed, double-blind study of social media falls out of the sky and into our lap. Maybe, just maybe, then we will stop using words like ‘may’ and ‘can.’

But until then, we’ll:

whine that researchers haven’t done enough to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that social media IS harmful to children;

pretend that we care about the kids who are suffering and the parents who have no idea how to help them; and

winge about tech companies, that they haven’t provided enough data — even though we asked them nicely! — to prove that their products are harmful.”

OF COURSE tech companies are dragging their feet on providing “the data.” Why would they want to implicate themselves and jeopardize their profits? They know exactly how addictive their products are; they created them that way. That’s why so many tech execs send their kids to technology-free Waldorf schools.

A few more gems from the advisory:

“Critical Questions Remain Unanswered”

“It is critical that independent researchers and technology companies work together to rapidly advance our understanding of the impact of social media on children and adolescents.”

Critical! Critical, I say!

“The relationship between social media and youth mental health is complex and potentially bidirectional.”

Bidirectional? What does that even mean?

“a lack of access to data and lack of transparency from technology companies have been barriers to understanding the full scope and scale of the impact of social media on mental health and well-being.”

Boo hoo. Data, schmata. I don’t need to “see the data” or read some report to know FOR CERTAIN that it is harmful. Not may be, not can be. IS. Spend some time in the presence of teens and you’ll know we have a huge problem on our hands.

The whole advisory felt like it was written by data-driven parenting expert Emily Oster (remember her?) with ChatGPT assistance.

Check out the handy recommendations not only for parents (create a family media plan!) but also for policymakers, tech companies, researchers, and even the children/adolescents themselves: nurture your in-person relationships by connecting with others and making unplugged interactions a daily priority!

“It can’t be on parents alone to manage this,” Murthy soberly told ABC News.

To that, I say: the hell it can’t.

God knows Peter and I made mistakes as parents; just ask our kids. But there’s one thing we haven’t regretted, not once since Charlie, our firstborn, arrived 25 years ago: we got rid of our television.

Yes, family members thought we were nuts. Friends and acquaintances doubted aloud how long it would last. All sorts of scolding came our way: “It’s part of the culture;” “they won’t be able to talk with friends about shows;” “they won’t fit in.”

But my favorite admonition was this: “You’ll be removing them from reality!!”

When I heard that, I knew we were doing the right thing.

As babies and toddlers, they had no idea what they were “missing,” but eventually they were old enough to notice that other people had televisions and we didn’t.

We needed to explain to them why. Here’s how we did it: [Excerpted from the first half of a two-part series I wrote about subliminal influence and propaganda:]

Peter (who was a hypnotist by that time, recently certified) gently explained to them that the tv is a box that tells stories, and some of them are true, and some of them are false, and some are a mixture of both. And that the people who make up those stories really want you to believe them, so much so that you do things, like buy stuff you don’t really need.

To really drive the point home, he put a cardboard box on his head and talked through a hole he had cut out. (Did I ever mention he used to be an actor in NYC?)

Some might say he was an agent of propaganda in that moment, and I would have to agree. But that’s the role and heavy responsibility of being a parent — you shape the beliefs of other human beings in your care. That’s why it’s so important to be aware of what you say and how you say it; they are drinking all of it into their own subconscious.

Our three little ones laughed a lot at their dad, but they got the message: the tv is not to be trusted, because it is the source of a lot of pro-panga-danga. [Their mispronunciation of “propaganda.”]

When we decided they were ready, they watched the occasional Andy Griffith Show or a Looney Tunes cartoon, as a special treat. They always wanted more — of course — but as my daughter Maddie put it, “that’s why children shouldn’t make major decisions.”

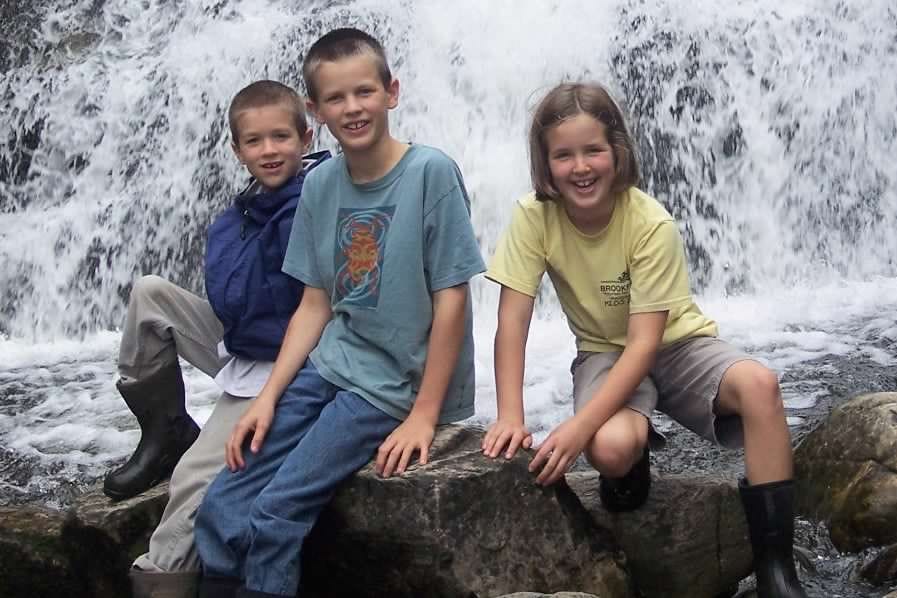

They spent most of their young lives outside, in the rain or snow or warm sunshine, building forts, sending their tiny bikes over homemade jumps, climbing trees, and exploring creeks.

Indoors, they read or listened to books-on-actual-tape, played board games, and narrated endless, improvised live-action stories with knights and queens and wooden castles.

They coaxed their tv-watching and video game-playing neighbors off their couches and into Capture the Flag games or lemonade stands. Interestingly, given the choice, the neighbor kids always seemed more than happy to join Team McLaughlin outdoors than remain glued to the set.

Rarely did I hear our children complain about their tv-free life, full of real-world experiences with human beings and nature. On occasion, they’d balk at going outside, but once there, they were content — so much so, I’d have to drag them in hours later, mud-spattered and complaining, to eat.

Thus the comment at the cocktail party: That’s the house with the kids always playing outside.

It struck me then as deeply sad, and now… well, it’s sadder still. Television seems quaint in comparison to the seductive juggernaut of tech entertainment now available on smartphones. How many more kids are indoors, alone, addicted to their devices, exchanging tangible reality for a virtual one?

I don’t want it to sound as though there was no downside to giving up the television. Our decision also meant we were giving it up, too. Plenty of other parents confided in us that they knew getting rid of it would be good for their kids, but they “couldn’t do without it.”

Pretty quickly, Pete and I realized we weren’t pining for it, though occasionally I did wonder how Party of Five wrapped up their series.

I faced a different challenge: being on deck with the kids, full-time. I do realize that we were extremely lucky; I was home with them for much of their young lives, a gift many cannot afford now. But because there was no “electronic babysitter” ready to relieve me, no plug-in solution to free me up to make a phone call or send an email, I went slightly buggy sometimes.

During those moments of frustration, I would inevitably laugh at myself, remembering that billions of parents throughout history — mainly mothers, let’s be honest — had somehow managed just fine.

It was hardest when they were really young. But as I encouraged them, even as tiny tots, to help me more and more with the day-to-day chores, I found my investment of time paid off beautifully. Tasks took longer initially, but as the kids’ capabilities grew, they needed me less and less. Eventually, they were able to work and play independently. It was a win-win: they gained skills, confidence, and self-sufficiency… and I could finally take a shower uninterrupted.

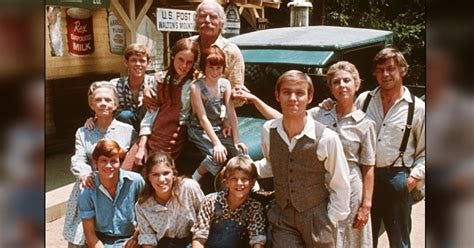

As our kids got older, we bought an iMac and watched movies together on it: The Blue Planet, Mr. Bean, March of the Penguins, that sort of stuff. Later still, we spooled out the string, letting them watch MacGyver or The Waltons.

Henry, the youngest, later told me that easing into programs and movies slowly, rather than experiencing a cold-turkey media blackout, helped him feel less deprived. A friend of his had had zero media exposure at home until he was 15, and when he finally was granted access all at once, he couldn’t get enough.

At long last, when our kids were 18, 16, and 14, Charlie came home from college and was shocked to discover that we had bought an actual tv in his absence and had put it in the basement. But by then, getting a tv actually felt anticlimactic. All three kids had cell phones by then — though each one had waited until the summer before starting high school to get one.

The older two never cared that much about their phones; Henry stood up and offered a very eloquent public condemnation of them at a showing I organized of the documentary Screenagers when he was a freshman in high school. Somewhat ironically, he went on to become the most attached of the three to his, necessitating some boundary-setting on our part.

Speaking of boundary-setting, I was heartened to read this article in The Free Press:

Perhaps the tide is turning, as more and more parents realize they have options they can take to help their kids, right now. They don’t have to wait for the government or big tech or the medical/academic establishment to step in with a solution; in fact, I’m not convinced those captured entities ever will.

Parents have tremendous power to influence their children’s mental health. The question is, are they willing to exercise that influence? As the article indicates, there are some who are.

I’m here to tell you: it’s not easy to swim against the mainstream, but like anything, it gets easier with practice.

Yes, our kids have had their “challenges” growing up televisionless. When they were toddlers, televisions in restaurants inhaled them. At grade school age, they had nothing to contribute when others reminisced about Teletubbies. In high school, they were the only ones writing about Andy Griffith for the English teacher who asked the class to write about their favorite tv shows. Their peers still can’t seem to understand what “I didn’t have a tv growing up” means, always interpreting it as “I didn’t have a tv in my own room.”

Even though Peter and I have never pushed them one way or another, each of them independently has chosen to forego FaceBook, Instagram, Snapchat, and all other social media. I can’t say it was the lack of tv growing up — there’s no way I could prove that causality — but I will say that all three of them grew accustomed to being “different,” and not having a tv was a big part of that difference.

I’d say they take some pride now, in going their own way. Whatever choices they make, they make to please their own internal compasses, not because everyone else is doing it. They are extraordinarily immune to outside influence — a mixed blessing when you’re their parent — but a damn miracle in a world where “influencer” is actually a job title.

That kind of independence is an unintended consequence, not only of growing up “different,” but also of growing up without staring for hours at a box of blue light that is actively trying to control your thoughts and behaviors.

Another unintended consequence? True social skills. If you ask them, they’ll all say they are actually grateful they spent their childhood and adolescence interacting with real, live, in-the-flesh human beings, because unlike many of their peers, they don’t have crippling social anxiety. They are comfortable carrying conversations with other people — in person.

Again, I can’t prove it — I have no DATA — but it makes sense to me that kids who interact primarily through social media would only know how to either make statements about themselves, like “I got a new car!” or make passing comments on someone else’s statement, like “awesome” or “so pretty” or “I’m obsessed!”

As Maddie put it, “It’s crazy… I feel like I have some kind of weird superpower, just because I listen, respond, and ask questions of others.”

Any kid in this country could have that same “weird” superpower. It used to be the norm, not the exception.

Just like I don’t need Freud to analyze the recent dream Maddie had, two nights in a row, in which a sinister dude was zapping everyone around her, putting them to sleep while she was somehow immune and able to stay awake, we don’t need Murthy and an army of experts to tell us that the mental health situation of kids in this country is dire.

What we need is Parent Power, lots of it, and soon.

What a gift you and Peter gave your children! Playing outdoors and playing make believe indoors are like air and water for children, yet they’ve become rare events for most. Beyond that, getting used to being different from an early age becomes like a super power as they get older, when mindless conformity becomes dangerous. Sometimes the most beneficial use of parent power is to just say no like you did. Thanks for this message. I share your passion on this topic; children have borne the brunt of the technological takeover as you clearly explain. Thank you for sharing this important information!!

👏 👏 👏 not gonna lie, super impressive! My kids love the outdoors (camping, fishing, hiking), but they also love their screens. Although, the youngest loses attention pretty quickly and would rather just listen to music. And dance! I couldn’t care less for a TV. We have a tiny one in the living room. I’d never put one in a bedroom. I didn’t have a televisión throughout my 20s, but now, I’d like air playing a podcast on it once in awhile. But I’m super impressed you did that with three young ones (relatively close in age). Kudos to you and Peter.