"Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television"

The Book Behind our Decision to Dump It, Part 1: Our Mediated Lives

This essay is a follow-up to last week’s Best Thing We Ever Did as Parents.

I realized, while diving back into this prescient book, that I don’t want to shortchange its wisdom by boiling it down too far. Each argument deserves some breathing room, and I also want to offer other relevant insights — those from other Substackers, as well as mine, too. This topic is too important.

So, off we go, into Our Mediated Lives. xox M

Mass Communication and Society was one of the very first classes I took in college. When my professor handed out the syllabus, I chuckled at the first title — Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. Really? Elimination?

But the author’s name — Jerry Mander — is what really got me. Was I participating in some psych experiment? This book had to be fake.

It was not.

Jerry Mander, a maverick advertising and public relations executive for 15 years, died less than two months ago. In 1972, in an attempt to move away from helping rich corporations get richer at the expense of public interest, he founded the country's first non-profit ad agency.

During his time there, he created an inventive, catchy ad campaign that is largely credited with stopping the U.S. government from damming the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon in order to generate hydropower.

After growing increasingly frustrated by the magnitude of his efforts compared to their results, he took leave of that agency in 1974. As he put it, “We felt as if we were throwing snowballs at tanks.”

Three years later, he published Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. It’s been a long time since I’ve read it, so I re-read it to remember exactly why I credit it with being the single largest influence on my desire to chuck the tv.

It’s an astounding, if dated, book; I recommend reading the whole thing.

The 1977 television world he describes — the one I grew up in — has changed. No more cathode ray tubes, no more test patterns. No more ABC, NBC, CBS, PBS primacy. Aside from the Super Bowl, no more communal gathering as a nation to watch programs.

We all know it’s changed, but here’s a staggering statistic to ponder: In 2021, overall media consumption among U.S. adults was estimated to be approximately 11.1 hours per day. That included smartphones, desktop, radio, television, and magazines.

There’s no doubt that television still holds sway over millions of individuals. It has infiltrated almost every public setting — even gas station pumps! — and overtaken private homes as well. Its ubiquity is stunning.

But smartphones have outstripped television’s ubiquity, as impossible as that might have seemed in 1977. Now, 85% of Americans own a smartphone, and as of March 2022, that’s where most people are now watching “tv.”

If we subtract radio and magazine time from the overall media consumption, we are left with this: Americans are consuming online media for nine hours and fifteen minutes daily. Granted, some of that time is spent answering emails, reading news, texting, or otherwise engaging the intellect rather than passively watching video content. But still. Nine hours of screen time?

46 years since Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television was published, technology has exploded, engulfing every arena of human endeavors: communications, agriculture, medicine, manufacturing, you name it. Now seems like a pretty good time to ask ourselves if Mander’s arguments were — or are still —valid.

But first, here is Mander’s opinion about technology in general:

“Most Americans, whether on the political left, center, or right, will argue that technology is neutral, that any technology is merely a benign instrument, a tool, and depending upon the hands into which it falls, it may be used one way or another.

There is nothing that prevents a technology from being used well or badly; nothing intrinsic in the technology itself or the circumstances of its emergence which can predetermine its use, its control or its effects upon individual human lives or the social and political forms around us.

The argument goes that television is merely a window or a conduit through which any perception, any argument or reality may pass. It therefore has the potential to be enlightening to people who watch it and is potentially useful to democratic processes.

It will be the central point of this book that these assumptions about television, as about other technologies, are totally wrong.”

Let’s look through an updated lens to see how this deeper philosophy behind his beliefs holds up within the context of this Brave Newer World, starting with his first argument. [Any quote, unless otherwise stated, is from Mander’s book.]

ARGUMENT ONE: “Television is a mediated experience.”

I don’t know many who would disagree with that statement. Yes, tv stands between us and the world around us, filtering our experience and understanding of the world.

Mander makes the case that we are highly susceptible to that mediation, because by suburbifying most of the landscapes that were once our home — forest, desert, marsh, plain, and mountain — we now live apart from the natural world in which we evolved.

“Our environment itself is the manifestation of the mental processes of other humans. Of all the species of the planet, and all the cultures of the human species, we twentieth-century Americans have become the first in history to live predominantly inside projections of our own minds.”

Living in that “artificial, reconstructed, arbitrary environments,” we have lost direct experiential knowledge of the infinite variety of the natural world, a circumstance that has slowly caused our conscious awareness to dim. How has that dimming happened?

Mander states that all five senses (plus instinct, intuition, feeling, and thought), “combine to produce conscious awareness, the ability to perceive and describe the way the world is organized,” and that a change in one aspect of human perception affects all the others.

Our five senses, he argues, developed “in interaction with the multiple patterns and influences of the natural environment.” None of our five senses occurred by accident. He gives as an example human eyesight, claiming that the interaction between our eyes and their environment is what created the range of abilities we need: sight “co-evolved with the ingredients around it which it was designed to see.”

If our eyesight can only be as functional as the environment offered during its development, then within a narrowed, manmade environment, it stands to reason that eyesight, like all of our other senses, has necessarily become less sensitive.

Our less-functional senses have undermined our capacity to discern reality, and therefore, we’ve become less reliant on those senses. Instead, we’ve become more reliant on other sources of information outside ourselves:

“There is little wonder, therefore, that we should begin to doubt the evidence of our own experience and begin to be blind to the self-evident. Our experience is not valid until science says it is.

Living within… environments that are strictly the products of human conception, we have no way to be sure that we know what is true and what is not. We have lost context and perspective. What we know is what other humans tell us.”

Whether or not you agree with his assessment of the functional degradation of our conscious awareness (and I’ll bring forward more evidence to support his case later in this series), I think it’s safe to say that during our evolution as a species, we have increasingly discerned what was true from the town crier, the priests, our neighbors… and later, from printed books, pamphlets, and newspapers.

In 2023, we now generally piece together what is true from consuming media… nine hours of it, daily. Mander offers a compendium of some of the “truths” we have consumed over the years. Here’s just a small sample:

“Mother’s milk is unsanitary… Mars has life on it. Technology will cure cancer. The stars do not influence us. Nuclear power is safe. Nuclear power is not safe. Mars has no life on it. Food dyes are safe. Saccharin is safe. Technology causes cancer… A little X ray is okay… We will have an epidemic of swine flu. Mother’s milk is healthy… Red food dyes are not safe. Swine flu vaccine is safe… Saccharin is not safe. Swine flu vaccine causes paralysis… And so it goes.”

I don’t need to offer recent examples of “truths.” I’m sure a few come to mind from the past few years, and many more if you’ve lived long enough on this planet. My personal favorite is the “lay your baby on her stomach to sleep” dictum, replaced years later with a stern “lay your baby on her back,” only to be reversed years later, with the “lay your baby on her stomach” directive once more. How ‘bout I do what seems best for my own kid?

Mander calls the narrative-shaping of truth “re-creation,” and maintains that it has channeled us, over hundreds of years, into narrower and narrower bands of experience, limiting our knowledge and perceived reality.

“…whoever controls the processes of re-creation effectively redefines reality for everyone else, and creates the entire world of human experience, our field of knowledge. We become subject to them. The confinement of our experience becomes the basis of their control of us.” [emphasis mine]

Perhaps, like me, you grew up feeling lucky to be “civilized.” And yes, it IS lucky to have a refrigerator filled with food from huge supermarkets to shop in, a house with central heat and AC, cars to drive and a dishwasher, and and and. But what have we traded for all those fortunate luxuries?

Mander would argue that we’ve traded our innate sense of reality, and “Because we live inside the new environment, we are not aware that any tradeoff has been made.”

Like so many around me, I’ve prioritized rational, intellectual processes and the institutions that fostered them over experiential learning. I thought I knew a lot because I read lots of books, paid attention in school, and watched television (not habitually, but enough), all the while failing to recognize the inherent limitations of all of those modes of learning and the limiting influence they were exerting on me.

I never considered that I might learn more from a walk in a forest than from the Encyclopedia Brittanica.

tells a beautiful story —as he often does — in a recent speech, entitled Staying Sane in the Next Five Years:“And we became alienated from beauty, from the divinity in all things, and instead related to Earth as a source of things for us, as resources, as things, not as beings.

And we became very lonely… the more that we were separated, the more lonely we became, the more crazy we got, living in this world of images, this world of representations unmoored from reality, taking on a life of their own, doing the craziest things in this separate universe that had no connection to physical reality and human reality and biological reality, to the point where that… reality is withering away.”

Mander spent a great deal of time with the Hopi tribes, attempting to help them rescue their dwindling culture from the maw of development. He learned quickly that television as a means of communicating their plight was not only inadequate, it was destructive.

No matter how earnest the reporter, the video medium somehow trivialized the experience of the indigenous people. It makes sense; how could you convey the totality of their connection to the land, their belief in the Great Spirit, the scope of their ancestral devotion in a 5-minute segment? Or even 10?

As soon as a human being is separated from an experience, the value of the experience diminishes. How many times have we all said, “You should’ve been there.” It doesn’t matter if the camera is high-res or the sound quality is superb, something is lost in translation.

A dear friend of mine could only be present through FaceTime for her father as he died. “It was better than not being there at all,” she acknowledged, “and yet.”

Yes. And yet.

I think Eisenstein is right, that reality is withering away. If nine hours a day are taken up by screens, how much of our waking attention is left for the real world? And if what we attend to, grows, then the opposite must be true as well.

I think back to that well-meaning person who warned me and my husband that if we jettisoned our tv, the effect on our kids would be “removing them from reality.”

In a sense, she was right. The reality she was referring to is real, but only in the way that a theatrical play or a fun house is real. That manufactured reality was exactly the reality we wanted to remove them from. We wanted our children to attend to the sky, the mud, the trees.

So we banished the boob tube and sent our kids outside… and they ended up just fine. (See Best Thing We Ever Did as Parents.)

Toward the end of Argument One, Mander mentions Aldous Huxley’s idea that totalitarianism could be achieved efficiently if the masses would enslave themselves through new technologies offering “a greatly improved technique of suggestion.” By the time Huxley died in 1963, that new technology was in full swing.

Research done in 1969 found that in less than one minute of television viewing, the person’s brainwaves switched from Beta waves (associated with active, logical thought) to primarily Alpha waves. (Alpha is a relaxed, receptive state — a light hypnotic trance — in which we accept images and suggestions into our consciousness less critically.)

When the subject stopped watching television and began reading a magazine, the brainwaves reverted to Beta waves. Clearly, tv fits the description of a greatly improved suggestion technique.

Huxley’s other criterium for efficient totalitarianism? The “joyful cooperation of the people being controlled.”

And here we can see what has changed dramatically since 1977. Television technology has evolved into something we carry with us, marsupial-like, into virtually all environments, all day and in the case of some, all night as well. My college-age kids describe classmates who FaceTime their boy- or girlfriends, then keep the “line” open next to them throughout the night so that they can sleep “together.”

What Huxley envisioned has come to pass: not only have we enslaved ourselves joyfully, we now actually pay for the privilege of that enslavement. The newest iPhone retails for $800, the newest Android, $650. And don’t forget the monthly data plans.

Here’s a short poem I wrote years ago:

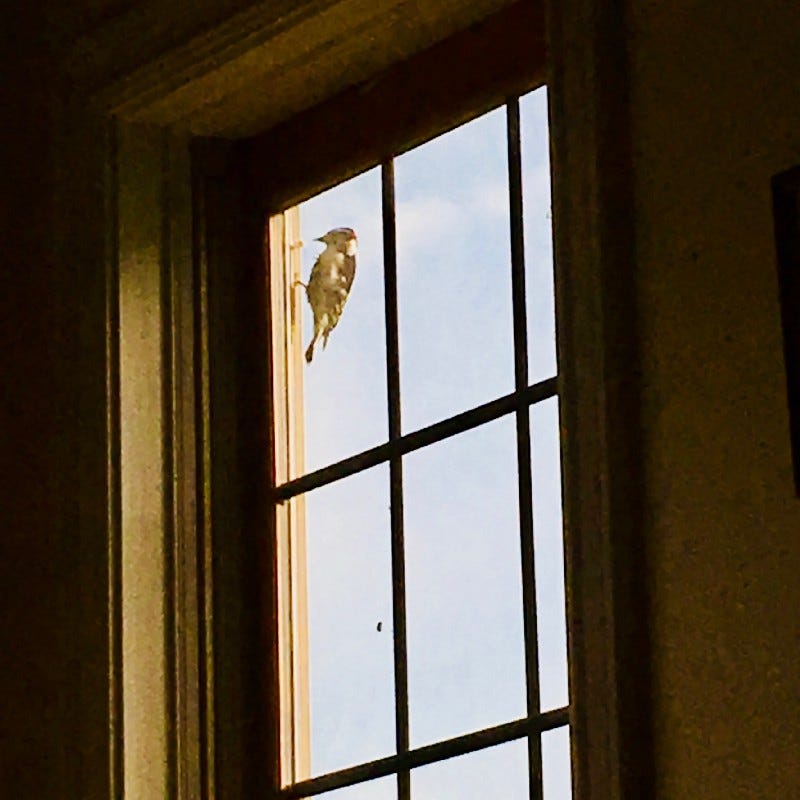

Find Something Real

A woodpecker clings to the

window screen

tap tap tap tap tap

again and again

coming up empty.

I want to tell her

That’s vinyl siding, dear. Go

find something real.

but I don’t.

Tap tap tap tap tap

Because we all have to

figure it out

for ourselves

In 1958 Harold Pinter wrote the following:

“There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false.”

Almost five decades later, in his acceptance speech for the 2005 Nobel prize in Literature, he said:

“I believe that these assertions still make sense and do still apply to the exploration of reality through art. So as a writer I stand by them but as a citizen I cannot. As a citizen I must ask: What is true? What is false?”

I agree with Pinter. So here’s the good news: we are not all woodpeckers.

There are many of us human beings figuring it out, many who see the chicanery of this vinyl-sided reality, this unmoored one, this sensory-deprived one that squeezes our field of attention like a boa constrictor and tricks us, daily, into valuing the wrong things.

is one such human being. He writes:Exchange meaning for control: that was the deal. Exchange beauty for utility, roots for wings, the whole for the parts, lostness and wandering and stumbling for the straight march towards the goal. That was the deal. Turns out it was a trap, and now look at us. Look at everything we know, and how little we can see. Look at us here, flailing, drowning, gasping as we sink into the numbers and words.

Another is

, who offers a highly practical solution:It isn’t real. The mediated world, the invented reality delivered to you through screens, increasingly wanders off into a deep space of its own making…It’s a manufactured reality that has to be kept afloat by the frantic efforts of an army of professional fakers. You can escape it… Specifically, you can escape it through the sophisticated technique that scholars call “driving around.”

Bray’s advice is excellent: get off your screen and into your car, and drive off into America. Spend time with other real, live human beings, even ones that might seem impossibly opposite. You’ll find that you have more in common with them than the media machine would like you to believe.

And here’s more good news, other than the Parents Saying No to Smartphones article I mentioned in Best Thing We Ever Did as Parents. I must say, I did a happy dance when I heard that the Metaverse tanked.

Cynics might say that the internet is so vast, so exponential in its constant expansion, that it’s pretty much a metaverse already. We didn’t need Zuckerberg’s version because, well, “we already got one.” (I’ll admit it — Monty Python was a television high point. Oh, the irony!)

An idealist (yep, that’s me — I’ll admit that, too) might say that Mander may not have seen all of the potential possibilities in his belief that “a change in one aspect of human perception affects all the others.”

What if the dimming of our five senses is affecting the others that make up conscious awareness — instinct, intuition, feeling, and thought — in a positive way?

What if those more subtle, internal guides have actually been strengthened by the diminution of the external ones, and are now stepping up to fill the vacuum left behind?

Maybe, just maybe, the ancient knowledge of what is true and real, the inherited instinct that still lives deep within our cells, our mitochondria, our DNA, rose up, looked at Metaverse and said, “that’s vinyl siding, dear.”

There really is no substitute for “being there,” is there? Whether it’s the wonders of the natural world or the idiosyncrasies of the people we love, a video cannot compare to being there, no matter how hi-res. It’s why we miss our loved ones so much when we’re geographically apart.

I’ve not yet thrown my smartphone into the Atlantic Ocean because I appreciate the far flung personal interactions it enables, but nothing can compare to the magical alchemy that occurs when we interact with each other simultaneously in real time, unmediated by technology.

Thank you, Mary. A very thoughtful, and beautifully written essay that is also incredibly timely.

I have not read that book, but have a feeling I don't need to. Besides, you're covering it!

I suspect too, that what we're in the midst of right now will push more and more of us into nature. Sad we seemed to require becoming so separate in order to re-orient, but as you note, we will eventually figure it out. Loved that poem too. Best, and thank you again.