This is the final essay of the series, started in Part I and continued in Part II. Read them both for a fuller experience of The Battle of Athens — it’s amazing, trust me — and to better understand my analysis of its relevance here in Part III.

The account is based largely on the fascinating The Fighting Bunch, by Chris DeRose. Unless otherwise stated, all quotes come from the book.

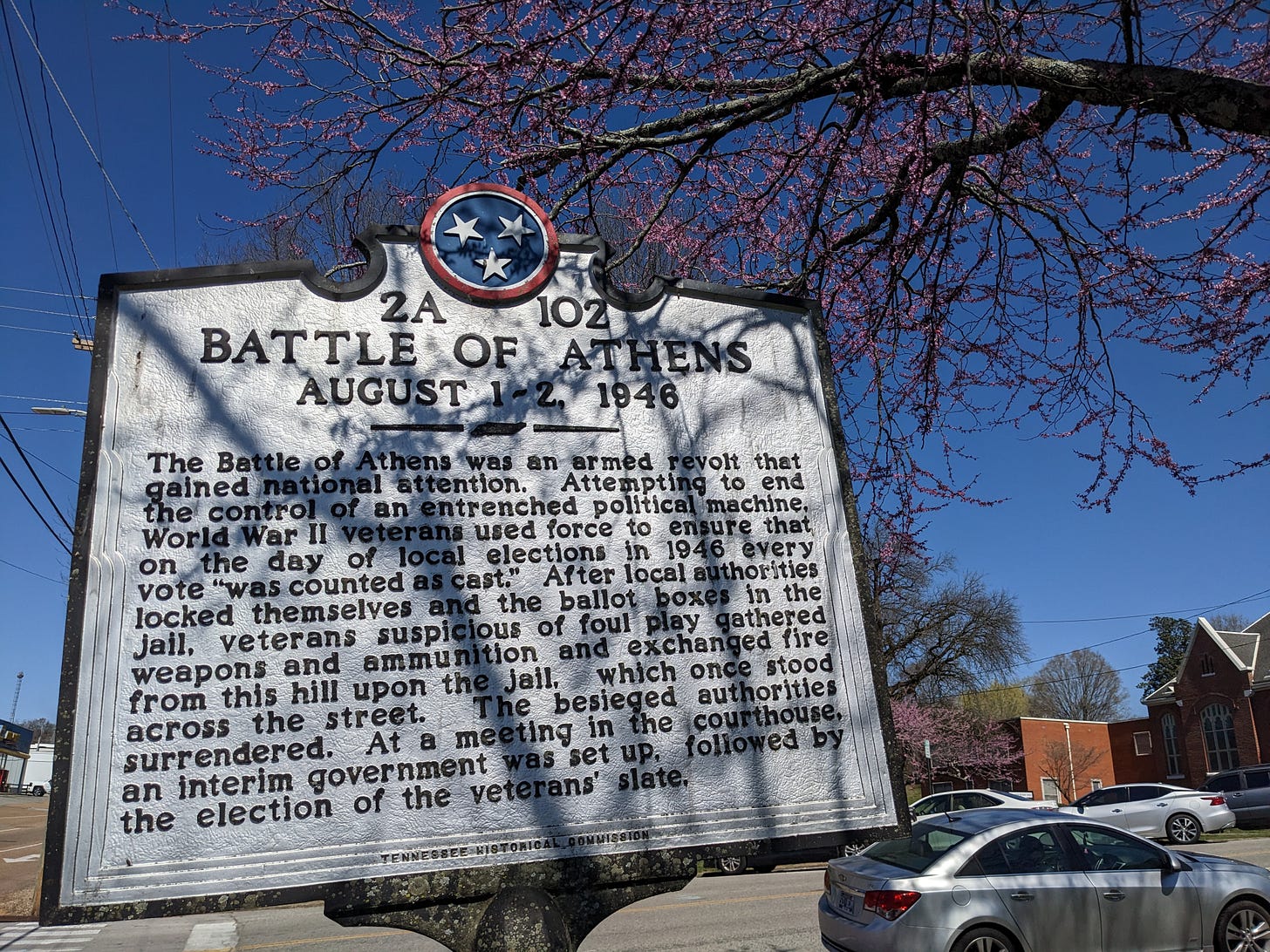

News of the successful armed rebellion of August 1, 1946 swept the nation, sending journalists to Athens, the seat of McMinn County, Tennessee. Everyone wanted to know: how did the small band of World War II veterans beat the odds, overtaking 250 hired, armed deputies and reclaiming their essential right to a free and fair election?

But the GIs involved — whether those who ran for election that day to oppose the “Cantrell machine,” or those who fought against the deputies — stopped talking.

Less than 24 hours after the event, Ralph Duggan — the GI who managed to instill restraint among his fellow rioting veterans with his well-timed eloquence immediately after the battle ended — made this statement to Bill White and the rest of his “fighting bunch:”

“Boys, listen. You broke in the armory out there and got all those guns. You wounded a lot of people, you blew up a lot of those cars. They’re going to be trying to prosecute you, but if you don’t say anything, they can’t find out who did it.”

The group apparently took Duggan’s words to heart. Some of the men never spoke about it again, even with their families. Bill White kept silent publicly for 20 years. When the attorney general in Washington (the same one who had ignored 1000 affidavits of voter fraud mailed to the Department of Justice in 1944 by the desperate citizens of McMinn County) sent investigators to Athens, their questions went unanswered — but not just by the GIs themselves; the townspeople zipped their lips as well.

Protecting the GIs who had made good on their promise of a fair election to the citizens of McMinn County turned out to be the citizens’ highest priority. That, and cleaning up the mess left behind — not just from the battle, though there were a lot of bullet shell casings and broken glass to be swept.

The town was in a different kind of disarray. Sheriff Mansfield had slipped out during the chaos and high-tailed it to Chattanooga, where he asked for “protection” at the Hamilton County jail, while Paul Cantrell had escaped the mayhem and sought asylum at an even more unlikely place: the Quisenbery Funeral Home.

Marcus Quisenbery was no Cantrell fan, but he was a member of the Blue Lodge Chapter of Free and Accepted Masons — as was Cantrell. As The Fighting Bunch states, “members of this brotherhood were bound by ancient rites to give succor to one another. Quisenbery drove Paul Cantrell out of Athens in the back of his hearse.”

With Mansfield and Cantrell gone, all the deputies locked up in jail, and the election still not finalized, there was essentially no government in place in McMinn County.

The townspeople of Athens selected a commission of three well-respected townspeople to run the place temporarily, until the votes could be tallied. Those three asked the GIs to keep the place safe, which they did, and then some. They set themselves to the task of cleaning up the “stepchildren born of politics:” the illegal gambling establishments that Cantrell had allowed to proliferate and prosper.

Aside from a rumor that Mansfield was mounting a retaliating attack (which did not materialize), over the next few days the town began to settle down. On August 4th, Mansfield tendered his resignation to Tennessee’s Governor McCord, who accepted it upon his return — he had been in Monteagle, TN (about 100 miles away from Athens) during this whole time, enjoying a week of vacation.

McCord, rightly so, faced charges of inertia, which he tried to sweep under the rug with statements like “It’s over, isn’t it? It worked out admirably.” I imagine no one in Athens was sorry to see him lose his bid for re-election two years later, the first defeat of a Crump-backed candidate in a major state election in over two decades.

Five days after the rebellion, in a courtroom spilling over with veterans and reporters from across the country, ballots from the fairly-run precincts were finally tallied and the results announced: all five men who ran on the GI ticket were elected. As the Post-Athenian wrote, “GI CANDIDATES SWEEP TO GLORIOUS VICTORY.”

The three-person commission voluntarily disbanded after its 72 hours of service, and later that day, when Knox Henry was officially installed as the new sheriff, he made these remarks:

“We have accomplished what we started out to do. We’ve broken the grip of the political machine that has ruled McMinn County for ten years without regard as to the wishes of the people in how their government was to be run… We regret that the gunfight at the jail had to happen… Our only alternative was to use force… there will be no trouble of this kind at the next election… We really intend to have a clean, honest government — one run on the best principles we know — of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Not everyone agreed with Henry, however. Some newspapers condemned the methods the GI employed to restore voting rights, saying that citizens showed not enough faith in democratic institutions, or that violence such as that can be misdirected, or that the men shouldn’t be excused just because they were veterans.

Over time, however, the news cycle moved on… and Athens did, too.

Cantrell’s machine dispersed, with many of its members relocating to other states. All in all, 28 officials resigned. “Boss” Crump took out half-page state-wide newspaper ads to claim that he had no ties to the Cantrell machine — a claim that the Associated Press deemed “pathetic.” Crump, to the sorrow of no one, went on to steadily lose control over Tennessee’s politics.

Mansfield made his own fruitless attempts at reputation repair, spinning absurd yarns to the press about the events that day, then packed up and moved to Atlanta, where he lived out the rest of his days.

Windy Wise, the deputy who shot Tom Gillespie point-blank as he attempted to cast a vote, was the only deputy convicted out of the 250 present on Election Day. He served one year in prison, out of a potential three.

A local judge ordered the grand jury to investigate every single crime of the rebellion, yet except for Windy Wise, there were no indictments. J. Edgar Hoover followed up by sending an FBI special agent to get to the bottom of it all: was the armory raided? Who raided it? Were guns or ammunition taken? Was anything still missing?

The men who had the answers to those questions stonewalled the agent as effectively as they had the news reporters. No one — whether they were GIs or not — seemed to know anything at all, but they “promised” to report anything they learned to the FBI.

Later, Bill White said, “We thought we were going to be prosecuted. The only reason we didn’t was because the sentiment of the public was behind us.”

The town that called itself “The Friendliest City” proved true to its name. The people of Athens were determined not to let the rebellion define or divide them… and they didn’t.

Paul Cantrell’s grandson, Paul Willson, became “a beloved and respected member of the community,” maintaining close relationships with the men of the GI ticket. Willson considered Bill White a personal friend.

Shy Scott, one of the GIs who was held hostage by deputies in the jail, was prepared to play himself in a movie version of the battle but backed out, saying that “reconciling the community was more important than fame.”

The jail was sold to a developer in 1953 and paved over to become a parking lot.

When I stopped in to explore Athens last month — the visit that spurred this series of articles — my conversation with the shop owner made it clear: there is still a taboo against talking about the rebellion. Like the paved-over jail, the Battle of Athens is an event that has been buried, for reasons given such as “friendliness,” “reconciliation,” and “unification.”

Their desire to repair the social fabric that was rent by the event is admirable, even virtuous. As Chris DeRose, author of the Fighting Bunch says, “If the people of McMinn County could come together after all that had happened, there is hope for everyone.”

I agree with DeRose, and I do believe that reconciliation is next to godliness. But I also think there’s more nuance involved here. There are other compelling reasons to bury the story of the Battle of Athens — and those reasons are all about power.

I’ve already written about Crump and Mansfield’s efforts to literally rewrite their involvement in McMinn County politics; Paul Cantrell’s Wikipedia entry is laughably tiny. Here is its description of his 10-year reign of corruption, intimidation, and outright malfeasance:

“Active in the local Democratic Party, Cantrell was elected Sheriff of McMinn County in 1936. He was subsequently reelected in 1938 and 1940. Like his Republican predecessors, he built a local political machine. He was elected to the Tennessee Senate representing McMinn County's district in 1942 and reelected in 1944. He also served as county judge from 1942–1946. A powerful and influential figure, he served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1944.

His political power was broken in 1946 in the ‘Battle of Athens,’ a rebellion led by war veterans. After the battle, he remained in McMinn County and worked for the Tennessee Natural Gas Company.”

Isn’t that astonishing? And yet, it’s not… when you consider that Cantrell was the youngest son of the richest man in the county, and that at the time of the rebellion, he still owned and operated Cantrell Bank, among other businesses. I doubt he was too keen on having his name dragged through the mud, or his dealings scrutinized. His financial security and his family’s reputation both rested on the disappearance of the story of the Battle of Athens.

And voilà! According to Wikipedia, he was an upstanding, productive elected official whose illustrious career was cut short by “a rebellion.” And now, his grandson Paul Willson, is “a beloved and respected member of the community” who donated $180,000 to the McMinn Performance Center in 2021.

I have no idea what kind of person Paul Willson is, and I have no reason to doubt that he is beloved and respected. I would also never begin to blame him for the actions of his grandfather — I’m not an advocate for that kind of indictment.

But don’t you find it interesting that the rich, powerful villain at the center of the story got off scot-free? I do. It makes me question: who else might have wanted the story of the Battle of Athens to go away?

How about the greater power structure of the United States?

The only post-Revolution rebellions I learned about in high-school American history were the ones that failed, and those defeats were painted as unjust insurrections, “quelled” (such a nice-sounding word, isn’t it?) by militia or the threat of it. There’s just no way that public-school U.S. history textbooks would tell the story of honest, earnest veterans of WWII arming themselves from the local armory and successfully overthrowing their local corrupt government. We wouldn’t want to give the little people any big ideas, now would we?

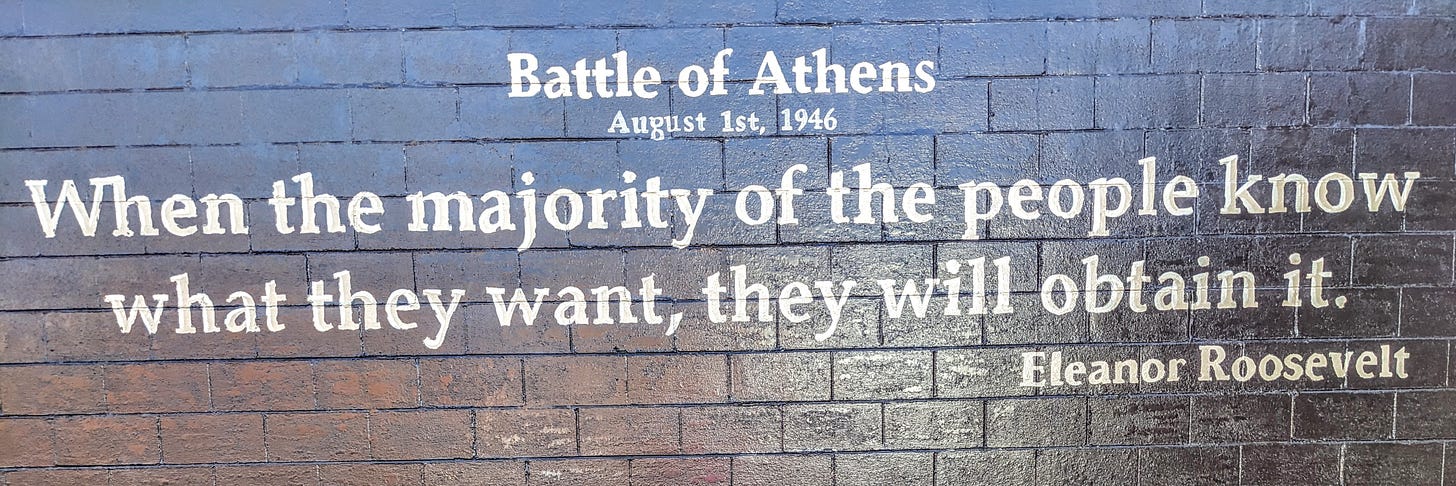

Yet Eleanor Roosevelt, after hearing of the Battle of Athens, made this statement on August 6, 1946:

We may deplore the use of force but we must also recognize the lesson which this incident points for us all. When the majority of the people know what they want, they will obtain it…

When the people decide that conditions in their town, county, state or country must change, they will change them. If the leadership has been wise, they will be able to do it peacefully through a secret ballot which is honestly counted, but if the leader has become inflated and too sure of his own importance, he may bring about the kind of action which was taken in Tennessee…

If we want to continue to be a mature people who, at home and abroad, settle our difficulties peacefully and not through the use of force, then we will take to heart this lesson and we will jealously guard our rights. What goes on before an election, the threats or persuasion by political leaders, may be bad but it cannot prevent the people from really registering their will if they wish to…

The decisive action which has just occurred in our midst is a warning, and one which we cannot afford to overlook [emphasis mine].”

She’s absolutely correct.

I could have synopsized the Battle of Athens in a few paragraphs, but I chose instead to devote three weeks to telling this story, for a very specific reason: I want people to know about this event because no one is taught about it in American history classes.

This event deserves our attention. It deserves to be known. It is emblematic of everything that the United States stood for when it fought its way into being. Put simply, it’s one of the greatest American stories of the importance of freedom and the willingness to fight for it.

It is also emblematic of everything that the United States has since said that it stands for.

How many, oh lord, how many times have we been told that we’re sending troops abroad to “fight for freedom?” How many fly-overs at football games have we all witnessed? How many fawning “thank you for your service” announcements? I don’t need to catalogue all the ways we have been propagandized to believe that the good ole US of A is some kind of World Superhero, a freedom fighter with nothing but justice and democracy in its heart.

Countless other individuals who have enlisted in the military have believed it.

Those GIs did. They signed up to fight in the Pacific and the Atlantic and in countless other places because they believed it. They lost limbs and they lost their innocence; they watched their friends die because they believed it. But they all thought it was worth it, because they were defending freedom.

How could anyone expect them to not fight for freedom in their own hometown?

“If it was worth going over there and risking your life, laying it down, it was worth it here, too. So we decided to fight.” —Bill White

Even as we are still being told that fighting for freedom abroad is our moral duty, the word freedom is simultaneously somehow being denigrated. When health freedom initiatives or free speech advocates are described by the main stream media, the word freedom is often put in quotations, like it’s some quaint, outdated notion at best, or a calculating rallying cry by “right-leaning extremists,” at worst.

It is neither. It is our divine right as human beings. I named this publication The Art of Freedom because I believe — no, I know — that freedom is the beating heart of life. Without it, as individuals and as a collective society, we are less than human.

I mentioned at the outset of this three-part series that I loathed history for most of my young-ish life. I’m embarrassed to say I gave lip service to Santayana’s famous quote — “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” — but secretly thought that phrase was for other people or for another, bygone time.

For me, history was irrelevant. I lived in a new era and an enlightened country, one beyond benighted wars, false flags, and high-level systemic corruption. Here in America we had already learned from the mistakes of the past. We were evolved.

The past two decades have lifted me out of that Disneyfied fairy tale and placed me solidly in a Brothers Grimm’s version instead — a place where human failings and wicked deeds are rampant, but so are courage and honesty and truth.

When my kids were in a Waldorf kindergarten, their teachers read them Grimm’s fairy tales. At first I was shocked; shouldn’t we protect them from scary stories? But soon I understood that if my kids never heard tales of human triumph over real fear and adversity — killing the ogre, say — what would they draw upon to meet adversity in their own lives?

I find myself seeking out US history now, warts and all. I want to understand how we got here, to this moment. What laws have been repealed in the past 50 years? Who has benefitted from the wars we’ve waged? Why did the creators of the Constitution include the 2nd Amendment? That last one is highly relevant to the Battle of Athens.

It’s true that the 2nd Amendment was probably created in part to ensure that slave owners could “quell” (there’s that word again) any uprisings of their slaves, since black men and women could not own firearms.

But the other reason James Madison offered up the 2nd Amendment was to ensure that U.S. citizens could fight back against a tyrannical federal government.

Right after the battle ended in 1946, the Philadelphia Record wrote:

“What else could they do? the Constitution of the United States says ‘the right of the people to bear arms shall not be infringed.’ …It seems reasonable to assume the Founding Fathers were thinking of more important things when they wrote the Constitution — perchance that the time might come when the bullet might be necessary to protect the ballot.”

I’ve always been a pacifist, but perhaps that’s because I’ve never had to fight for anything. I’ve never had to step over that line for the justness of a cause. When I read The Fighting Bunch, I came to believe: there really are things worth fighting for.

Major Carl Anderson said this to The News (New York) on August 6, 1946:

“…I hope that our country, especially those places that are as boss ridden as we were, will take hope from what we have accomplished here. I think we have shown how to clean out those dirty nests. Anyway, we’ve done it.”

The rebellion could have ended in a very different way. Remember, the National Guard was on its way to “put down” the uprising in Athens — what if they had? Ironically, we’d all probably know the story of the Battle of Athens.

But they didn’t.

The son of one of the GIs later said this about the Fighting Bunch:

“They led positive and productive lives, and they left a legacy that their families can and should be very proud of. In short, they proved themselves to be the very kind of good citizens that deserve a fair and honest government to represent them, which is all they had ever asked for in the first place.”

All citizens deserve as much.

Exactly why citizens must have guns . Great story . Thanks for writing.

Great series; if you continue in history writing I'd like to see an account of the Wilmington Coup of 1898, the only similar case to the Battle of Athens I've seen.