I’ve spent the past three weeks landscaping, aka clawing the soil around my house.

I now say “soil” thanks to the clerk at a local nursery, a bitter gal who took offense a few years ago when I blithely asked to buy a few yards of dirt. “Dirt? Um, no, we don’t sell dirt,” she sneered. “We sell soil, however.” I haven’t been back.

It’s a huge job, one that I’m embarrassed to say in years past has reduced me to tears, not because I’m averse to gardening or hard physical labor, but because the entire area is consumed by a certain kind of weed: horsetail.

I’ve fought a losing battle with this stuff ever since we moved into this house, 12 years ago. Every May for a dozen years, I’ve cracked the whip on Mother’s Day, the only day I could insist that the whole family join me in my sisyphean task, singlehandedly turning Mother’s Day into the most heinous of holidays.

Last year, to the utter delight of my family, I decided I just couldn’t care anymore about the horsetail – in May or any other month. Yes, I grabbed a few handfuls here and there before visitors arrived, but for the most part, I let them do their invasive thing.

My laissez faire attitude probably would have persisted were it not for the decision we made to sell the house (not because of the horsetail, though the thought of leaving it behind does lift my spirits). Turns out horsetail doesn’t have great curb appeal.

Going mano a mano with it over the past three weeks has given me lots of time to reflect on it, and on weeds in general. As I drifted into a weeding-induced reverie of sorts, lots of metaphors started arriving, much like the characters in a children’s book I read to my kids many times, many years ago.

The Flowers’ Festival, by Elsa Beskow, was a treasured story in our kids’ literary lives. Beskow is considered the Swedish Beatrix Potter, and many of her books figure prominently in the Waldorf early childhood curriculum. For good reason — they are often magical adventures into nature that highlight cooperation, community, and resourcefulness.

Like her other books, The Flowers’ Festival is beautifully illustrated and charming. It’s also one of those children’s books that, upon closer inspection, serves to reinforce some dangerous notions about social order.

Little Lisa, sad to be left at home when her grandmother goes to the Midsummer Festival, perks up when a Midsummer Fairy appears and invites her to come to the flower’s party. The Fairy puts a drop of poppy juice (interesting choice, no?) into Lisa’s eyes, and all of a sudden, Lisa can see all the flowers in the garden getting ready for the event.

Lisa watches as more and more flowers, sorted by their environment (meadow, forest, pond), arrive and make their way to the top of the garden where “Queen Rose” is seated on her “throne,” surrounded by the other flowers of her “court.”

Red flag number one.

When I initially read this book years ago, I was either too sleep deprived from child raising or asleep at the social order wheel, or both. Questions like “Who made her queen?” or “Why is there a hierarchy in the garden?” did not dawn on me. I accepted that Lady Lilac should be amongst the court and that the Common Daisy should not. I accepted that Madame Pansy should be attended to by the lesser Violets.

Why is that? Why did I accept that the natural world should mirror the laws of human construct, instead of the other way around? Why did I believe that the powerful are powerful for some divine, natural reason? Because I grew up inside a system, and when you do that, you cannot see the system. The Queen of England deserves her position, because… well, because someone has to sit on the throne. Don’t they?

I don’t think Elsa Beskow was perpetuating hierarchy on purpose, just as I wasn’t trying to prop up the system by reading a sweet story about garden flowers to my children. My earlier essay Our Lives in the Tank talks about this phenomenon, so enough said. But I do think that it’s important to keep pulling back the curtain, to show all the subtle, insidious ways that we are indoctrinated without knowing how or even that it’s happening.

And I want to bring your attention to this book’s message in particular, because it’s a perfect lead-in to the insights that follow, gained from my conversation with Jennifer Schlee, permaculturist and all-around weed enthusiast.

Back to the book.

Lisa is surprised to see all of the houseplants cautiously arrive at the party, because they are afraid of “draughts and the cold night air.” Queen Rose gives one of them a cobweb shawl, so the storytelling can begin.

Red flag number two.

Let’s consider the concept of “houseplants.” That’s right, those are the plants that are imprisoned in a hostile (to them) climate far from their natural homes.

How absurd/sad/ironic is it that these plants, having been raised in the wrong environment, actually now believe they’re not able to withstand the elements, when the reality is that if they were planted where they are supposed to be, in their natural habitat, they wouldn’t be afraid of the effing night air?

Pardon me, but does anyone else see an analogy to our current lives in society? Rather than being given the tools to become strong, healthy, vital human beings, able to withstand challenges of any sort, physical or emotional, we are relentlessly told that we are frail and incapable, in need of the proverbial cobweb shawls provided happily by pharmaceutical companies and hawked by Madison Avenue.

Lisa does not see the analogy. She’s distracted by the hubbub at the garden gate. Queen Rose asks, “What’s all the noise about?”

“Weeds!” says Mrs. Beetroot, then continues, “Scoundrels and beggars and ragamuffins, all trying to get in — we’ll put a stop to that! We’d never get rid of them if we let them in.”

And then my favorite line in the whole book, that I somehow blindly ignored way back then:

“But we’re flowers, too,” cried the weeds. “We’re no worse than that cornflower.”

Indeed.

Queen Rose, of course, has a solution to the weeds wanting to join the party. But first, let’s take a closer look at those weeds, with the help of my dear friend Jenny.

Regular readers might recognize her name from my Motorcycle Insights piece, as my former college roommate and partner in crime. Since those days, she has worked in product design, facilitated at Stanford Business School, and trained in trauma-healing. She also received a masters in Economics for Transition from Schumacher College and holds a certificate in Permaculture Design.

Now, however, she is devoting her time and energy to a five-acre plot of land in Washington State, encouraging its transformation from an empty lot into a self-sustaining, harmonious habitat. Her (and her partner Denni’s) vision for the place is ambitious: to create a “Presence Sanctuary,” as they call it, a permaculture laboratory and learning center where visitors may, among other things, connect, commune, cultivate, alchemize, and harmonize — and not necessarily in that order.

Jenny adores weeds. As we ambled through the property on a visit in 2020, she continually stopped to grab some leaf, or shoot, or green scraggly bit, name it for my benefit, then pop half in her mouth and offer me the rest.

She adds weeds to salads and soups, trumpeting their overlooked nutritional impact. One evening we sampled boiled thistles, eaten like teeny tiny artichokes. I can’t say I loved them, but hey, with drawn butter I’ll eat almost anything.

And she is right: weeds like purslane, mallow, and chickweed have ridiculously high nutritional value. So why don’t we eat more of them? Because, she says, they’re not marketable. They don’t transport well and they’re not pretty, especially when cooked — which a number of them require to be edible. (I’m looking at you, thistle.)

Weeds are also incredibly resilient. Their deep taproots allow them to survive in even the most desolate conditions. They often have more than one way to propagate — seeds and rhizomes — and will therefore always outperform the single-mode reproducers. That’s why the horsetail in my garden is so fierce.

Jen sees weeds as scrappy plants that don’t need special care, underdogs that take on the qualities of the flora around them in order to survive. She also points out that most plants in our gardens are transplants from somewhere else, and that the process of transplanting always disrupts a plant’s roots, which led us to posit that the voluntary nature of weeds -- they choose where to plant themselves – might make them stronger. Seems plausible.

If weeds have all of these unrecognized virtues, and are just as nutritious as what we call vegetables, then what, really, are weeds? A common definition is “a plant that is growing in an area where it is not wanted.” Really? Wanted by whom? Given that definition, I’d say that weeds are in the eye of the beholder.

“Once in a golden hour

I cast to earth a seed.

And up there grew a flower

That others called a weed.”—Alfred Lord Tennyson.

But that’s not what Queen Rose believes.

In her infinite wisdom and beneficence, she says to the weeds, “I suggest that you sit along the edge of the ditch outside the garden. Then you can hear and see just as well, as long as you sit quite still and don’t disturb the party.”

At this point in the book, so many red flags pop up that I have to stop counting.

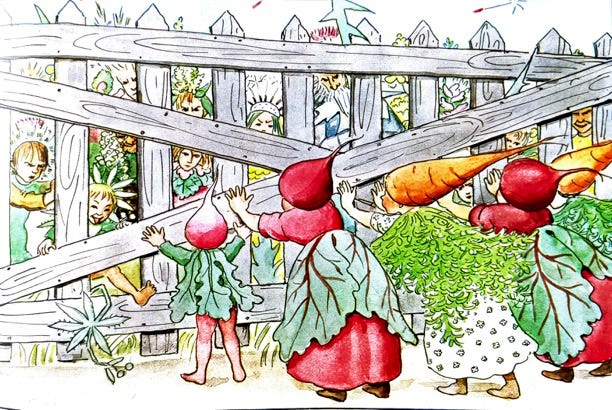

This illustration says it all:

Great solution! Separate but equal. Wait, where have I heard that before…?

The Queen then also “suggests” that the nutritious Mr. Thistle stand guard at the gate to deal with “troublemakers.” The weeds, including Mr. Thistle, comply. No surprise there. Can you really call it a suggestion when it’s coming from a Queen?

Everyone is now in their “correct” place: the Queen and her court luxuriate at the top of the garden; the lesser plants drift somewhere lower down; and the weeds are sequestered outside the gate, surveilled by a powerful, prickly, state-installed Benedict Arnold.

“At that, calm was restored, and the story-telling could begin.” Of course it’s time for storytelling. Telling stories is how we make sense of the world. It’s also how we reinforce our understanding of — and more important, our standing in — the world.

On cue, with the approval of Queen Rose, a fawning bumblebee and three bootlicking birds step up to tell some placid tearjerkers. My favorite is the garden warbler’s yarn about how the regal wardrobe of rich, important Madame Pansy is rescued by her little bumpkin cousins, the Violets, and how much nicer she is to them now that they made her more presentable.

Ah, yes. Some sweet, harmless stories to make everyone feel safe and happy in their respective roles. The Queen’s on her throne, the weeds are outside the gate where they belong, and all’s right with the world.

Until “the shrill voice of a cheeky sparrow” pipes up. He claims to have a story he thinks his friends outside the gate will like. He starts by saying:

“Once upon a time, there was a great gang of raggedy, higgledy piggledy weeds, all poor, all noisy, all cheerful and not at all good.”

It’s an auspicious start to curry favor with the Queen, but his tale soon goes off the propriety rails by expressing empathy for the dismal treatment of the weeds. When he finishes his story, the real weeds, ostracized beyond the gate, roar in approval.

Lady Peony complains to Queen Rose, “Can’t you get rid of that rabble?” and a riot ensues when a young Burdock weed boy hurls burrs at the flowers. Old Mrs. Nettle shows her fealty to the Queen by offering to thrash him, and hauls him off. No one objects.

Queen Rose fans herself to cool down from all of this insurrection, and gratefully accepts a frog’s proposal to sing a lullaby. Why wouldn’t she? What better way to counteract the disruptive, treacherous effects of the sparrow’s story than to lull the populace into complacency?

Go back to sleep, everyone. Forget what you just heard. All is well.

The Flowers’ Festival reinforces both a stratified social order (your garden-variety monarchy, pardon the pun) and othering (weeds are not like us; they are inferior and disruptive) – just as our societies do. World history shows us evidence of othering on a massive scale — toward indigenous people, black people, and Japanese Americans here in America, toward Jews in Europe, and toward Muslims in France, to name just a few.

More recently, after 9/11, the U.S. government cast suspicion on anyone of Middle Eastern descent. Just seven months ago we heard Justin Trudeau question whether the rest of Canada needs to “tolerate” the unvaccinated.

It’s a slippery slope, isn’t it? As soon as you call out a specific group of individuals and lay blame at their feet — any kind of blame, for anything — you are effectively putting them behind the garden gate and condoning their excommunication. You are saying, “They are different. They are lesser. They don’t belong.”

The irony here, from the plant world point of view, is that the very ones being cast out are often the strong ones, the resilient ones, the ones who are determined to persist. Their taproots run deep.

From the governing point of view, those are the ones to fear, for the same reasons and more. They’re wild, unmanageable, and their roots tap into something more powerful than water: their beliefs, or a higher power.

Yet even the most novice organic farmer knows that health is born of diversity. When plants are allowed to mingle, as they do in nature, they protect one another from pests, provide nutrients to one another and the soil, and work synergistically for the benefit of the whole.

Any farmer knows that the more we separate into monocultures, the more susceptible we become to disease. This is why factory farming — 1000 acres of corn, say, or wheat — requires huge amounts of pesticides and fertilizer to keep it viable.

I’m not the first person to suggest that a populace that embraces diversity of all types — religious, political, cultural, economic — has more fortitude.

Yet if I tell you to close your eyes and imagine a farm, do you see row after row of the same vegetable? What about imagining a flower garden? Is it an orderly, weed-free, well-mulched bed? Why do we persist in adhering to our inherited standards of garden order, both literal and metaphorical, that neatly defined rows are better than a messy hodgepodge?

Part of the problem is that we’ve always thought of nature and man as separate, with nature playing the understudy. The Bible may have had something to do with that:

Then God said, “Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; and let them rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” —Genesis 1:26

That pretty much covers it all, doesn’t it.

Perhaps at the time the Bible was written, the “take, take, take” philosophy was sustainable. But setting aside the hierarchical messaging of that passage, and looking at from purely a practical point of view, it’s crazy to think that the entire purpose of the earth is to serve humankind. Let’s face it: the earth can and will shake us off any time she decides she no longer can support our dominating, parasitic behavior.

So what’s the answer? I’m so far from an expert on this topic that I would never claim to have it. What I do have, however, is a burgeoning appreciation for permaculture – something I never really understood until my visit to Presence Sanctuary.

Jenny has assured me that fully explaining permaculture here would take up the entirety of this essay, so here’s a link to explore more. My over-simplified definition: permaculture observes how systems work in nature, and then seeks to reproduce those systems for the synergistic benefit of all.

To put it in The Flower Festival terms: there’s definitely a party going on here; ALL the plants are invited, including the weeds; and Lisa can join in, but the party is not JUST for Lisa.

It’s a staggeringly big concept. It’s not just organic gardening, it’s the relationship between plants (everything that grows), people (you, me, and everyone else), animals (from livestock to microscopic soil organisms), and all possible permutations thereof.

It’s like an infinite square dance, with each entity do-si-do-ing with every other entity. There is a level of cooperation, complexity, communication, and even sentience that is completely beyond our comprehension. It is interdependence on a mind-boggling scale.

Dr. Bernardo Kastrup, author of the book “Why Materialism is Baloney” (love that title!), stated in a recent interview: “There are a great many things about nature that are flat-out not only not perceivable by us, but inconceivable by us.” He explained why, saying, “Evolution would only equip us with the sensors…that present information relevant to our survival.” It might shock many of us to realize what he is really saying: our survival is not the universe’s top priority.

Many of us think nature is here to serve us, rather than the other way around. Permaculture seeks to reverse that misperception by really observing, listening, and communing with the land. In doing so, we may actually provide sustenance for ourselves – not as the primary directive but as a fortuitous byproduct.

There are a lot of dire predictions these days about farming crises and food shortages. We are also told that technology will save us: genetic modification of plants and animals, hydroponics, lab-grown meats, processed bugs. Something about these solutions makes me think of the lyrics of If I Ever Lose My Faith, by Sting:

I never saw no miracle of science

That didn't go from a blessing to a curse

I never saw no military solution

that didn't always end up as something worse

What if the solutions to our planet’s problems are simpler, more local, more humble and more community-based? What if nature is trying to tell us:

Follow my lead. Embrace wildness. Let go of your hubris and your need to bend me to your image and your will, and we will get along famously.

As I write this, I’m sitting in a park with my dog Samson, waiting while our house is being shown once again to prospective buyers. Before I left, I noticed horsetail tips nosing through the inches of mulch I painstakingly laid down 10 days ago. I laughed, and not just because they’ll soon be someone else’s horsetails.

I laughed because questioning my unconscious beliefs about them freed me to see them differently. They are no longer a nuisance requiring removal. They are, as the weeds cried, “flowers, too… no worse than that cornflower.”

May we all open up to the power and beauty of outcasts and reclaim them as part of the family. The health of the planet may well depend upon it.

Wow...this was a long one to get through but also one that made me stop and think...and think...and think some more. To me, I enjoyed thinking about weeds as a reminder to never allow people to tell us how to think...how to judge... That definitely hit a nerve with me as I thought about how much my father tried to mold me into what he thought all Americans should become...I was a weed to him but in my mind, I was/am a glorious flower!

Mary! OMG, I LOVE this! I have been on the hunt for Horsetail on the land here. It's such a beneficial weed/plant. And the fact that it was so tenacious and persistent growing near you migh just be that you could have benefited from its medicine. I want to go back and re-read this when I have more time. I loved it! 💚